The world order is changing, with the outcome uncertain. What power configuration could the EU face internationally in 2035, and how can it prepare for this? In an uncertain and complex present day, it is of great strategic importance for decision-makers to prepare for different futures. We have therefore mapped out six scenarios for the world (dis)order in 2035:

1. “World Order Made in China”: China has established itself as the hegemonic power over the United States and dominates the world order.

2. “America Great Again”: The United States dominates the world order again, acting autocratically and often erratically under the influence of the MAGA movement.

3. “Two-Men Show”: Two powerful blocs, China and the United States, face each other in a fragile balance.

4. “Five-Body Problem”: A polycentric world order with five largely self-sufficient, protectionist power centres – the United States, China, Russia, the EU and India.

5. “Authoritarian International”: An authoritarian-populist power structure, supported by personal diplomacy and ideological proximity.

6. “Beyond States”: A world in which state authority is waning and non-state actors are shaping the global order.

We also identified fields of action for the EU that are applicable to all scenarios. The EU can prepare itself to the best of its ability for various scenarios over the next ten years by taking consistent, collective and, above all, immediate action in four fields:

1. Effective decision-making: The EU should break down decision-making deadlocks by making strategic use of minilateral formats and underpinning them with a shared set of values. At the same time, it should expand partnerships with (like-minded) third countries in order to increase the EU’s international influence.

2. Credible deterrence: Europe should strengthen its defence capabilities through closer integration of national armed forces, joint procurement and innovation structures, and better coordinated investment – in close coordination with NATO.

3. Strategic resilience: The EU should prioritise critical key industries and technologies and create targeted strategic indispensability by establishing technological ecosystems and positioning itself in selected market and technology niches.

4. Social sustainability: EU institutions and Member States should strengthen social cohesion through credible narratives for the future that legitimise reforms and provide guidance, even in difficult transition phases.

Inaction will have consequences: The EU could break apart, be worn down or simply become irrelevant as a geopolitical actor.

Introduction

China’s rise, the United States’ withdrawal, Russia’s attack – the world order is changing. Weakened multilateral institutions and increasing domestic political polarisation are shaping the international landscape. The world order has not only become more unstable, but also structurally more volatile. One thing is clear: There will be no return to the liberal, US-dominated post-Cold War order (for the time being). It is unclear what new (dis)order will emerge over the next decade and what this will mean for the EU.

Against this backdrop, strategic foresight is increasing in importance. Systematically examining several plausible futures can help decision-makers to better assess uncertainties and remain capable to act even under changing conditions.

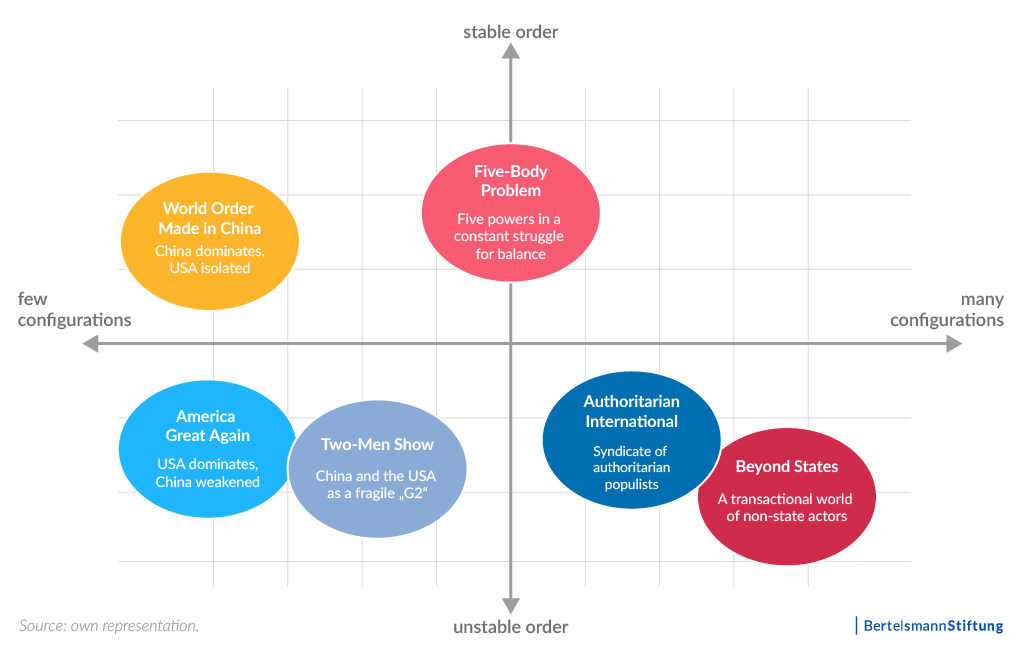

In a scenario process, we therefore worked with the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI and experts from business, academia and politics to develop six scenarios for the world (dis)order in 2035, which differ in the number of power centres and the degree of stability (see figure). In this process, we also identified four fields of action applicable to all scenarios. If the EU takes consistent, collective and, above all, immediate action in these fields, this will best prepare the EU to assert itself as an, at least partially, independent actor capable of taking action in different international configurations by 2035.

The scenarios should not be taken as concrete forecasts or predictions. Rather, they aim to serve as a strategic tool for decision-makers and anyone concerned with the world of tomorrow, to explore different possible futures and sound out their own scope for action.

Six scenarios for a world (dis)order in 2035

Scenario 1: World Order Made in China – China dominates, USA isolated

By 2035, China has established itself as the dominant global actor, while the United States has largely withdrawn from international leadership. The international order is organised within a Sinocentric system: Multilateral institutions continue to exist, but have been reformed according to Chinese guidelines, and primarily serve to showcase Chinese power. Climate policies function less as a multilateral control instrument and more as a bilateral lever of geopolitical influence. Regional and supraregional formats such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the BRICS states (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), or informal authoritarian alliances such as that between China, Russia, Iran and North Korea (CRINK), support China’s hegemony. Western alliances such as NATO are losing importance.

Economically and technologically, the world is heavily dependent on China. Value creation, innovation and key technologies – from artificial intelligence and semiconductors to green tech, digital infrastructure and critical raw materials – are concentrated in China and its regional environment. The renminbi is the global reserve currency. China strategically exploits these dependencies without providing concrete security guarantees. Security is primarily enforced through economic pressure, digital control and surveillance. Military force remains the exception.

Implications for the EU

In this scenario, the EU risks losing political, economic and technological influence. Internal fragmentation and bilateral initiatives by individual Member States vis-à-vis China could further weaken the EU’s capacity to act. At the same time, risks arise for economic autonomy, technological sovereignty and liberal democratic standards.

The EU can counter this by strengthening its internal cohesion, becoming more strategically self-sufficient and using its internal market as a source of power.

Minilateral partnerships and selective cooperation with China – perhaps in the fields of climate and the environment – ensure limited room for manoeuvre but remain prone to conflict in the long term.

“Countering” means positioning the EU so that it remains capable to act and strategically viable should one of these scenarios become a reality. To this end, it is important to establish the necessary conditions at an early stage while continuing to actively utilise the scope for action within each scenario.

Scenario 2: America Great Again – USA dominates, China weakened

By 2035, China will not have succeeded in stabilising its economic and political model. Declining growth, growing social tensions and the loss of political legitimacy will plunge the Communist Party into an existential crisis. As a result of this development, the international order will once again be unipolar, with the United States as the leading power. The economy will once again be oriented towards the United States, with China marginalised as a production location and technological supremacy clearly in US hands. Under the influence of the MAGA movement, the United States will act autocratically and often erratically. Its hegemony will be rooted primarily in military strength and financial superiority. Extensive re-dollarisation of the international financial system reinforces this dominance. International organisations continue to exist but are losing political weight and are acting predominantly on an ad-hoc basis under US leadership.

Security is primarily ensured through dependencies, not collective guarantees. NATO has become irrelevant. Despite its relative weakness, Russia remains revisionist, while the United States deliberately maintains or expands economic and technological dependencies.

High-tech, AI and data-based business models are concentrated in the United States. Europe benefits from reindustrialisation and onshoring, but at the same time falls into new dependencies. Climate policies are losing priority worldwide: The decline in Chinese emissions provides short-term relief, but in the long term, climate impacts exacerbate inequalities, migration and resource conflicts. The United States secures strategic raw materials for the green transformation primarily in accordance with its own interests.

Implications for the EU

The elimination of Chinese competition could give the EU some economic breathing space in the short term. At the same time, however, its political vulnerability to the United States has grown and its strategic autonomy has been significantly curtailed.

The EU can counter this by strengthening its industrial base and defence capabilities, responding reciprocally to trade barriers, and limiting economic and technological dependencies. In addition, a new realism is needed in transatlantic relations, without abandoning them completely.

Scenario 3: Two-Men Show – China and the USA as fragile “G2”

After a period of escalating tensions, the United States and China have agreed on pragmatic coexistence. Both sides acknowledge that direct conflict would prove disastrous for them and informally accept each other’s spheres of influence. However, the resulting bipolar order (“G2”) is fragile: It is based less on institutions or rules than on personal deals, power politics and mutual deterrence. A change in key actors or domestic political pressure in either country could destabilise the balance at any time.

The global economy is effectively divided into two largely separate technological and economic ecosystems. Value chains are being decoupled, efficiency is decreasing and costs are increasing, while social inequalities worsen. Universal rules are losing significance; in their place, delivery capability, technological sovereignty and political loyalty determine access to markets. International security is tense, especially in third regions. Multilateral institutions continue to exist formally but are being circumvented or exploited by the two power blocs. Climate policies also follow bloc-logical patterns: China is making strategic use of investments in green technologies, while the United States has limited capacity to act due to domestic political polarisation.

Implications for the EU

The EU may find itself caught between the power blocs and run the risk of being politically marginalised or economically blackmailed – for example, by being excluded from key technologies. At the same time, there are risks due to deindustrialisation, social tensions and the rise of populist forces.

The EU can counter this by positioning itself as an, at least partially, independent third actor. Based on internal cohesion, niche technological expertise and selected partnerships with (like-minded) third countries, Europe can secure room for manoeuvre and protect itself from being crushed between the major powers.

Scenario 4: Five-Body Problem – Five powers in a constant struggle for balance

In 2035, the global order is based on a delicate balance between five centres of power: the United States, China, Russia, India and the EU.

In terms of security policies, all five powers are heavily armed, including nuclear capabilities. There is no comprehensive arms race, as all have an interest in limiting nuclear proliferation. Proxy conflicts flare up mainly in contact zones between the power blocs. Rivalry is increasingly focused on critical resources such as raw materials, water, food security and skilled labour. These tensions are pragmatically contained between the five leading powers through barter agreements.

Economically, all blocs strive for strategic autonomy. Trade, value chains and innovation are largely organised within blocs, and are protectionist, with technological breakthroughs being shielded. The approach to climate and environmental crises also follows this logic: The five powers acknowledge the urgency but rely primarily on large-scale technical solutions such as geoengineering. Long-term sustainability initiatives remain limited.

Implications for the EU

Internal disagreements could cause the EU to adopt a hesitant, uncoordinated stance towards the other four geopolitical blocs. This would leave the EU vulnerable and undermine its ability to assert itself against the other actors.

The EU can counter this if it succeeds in securing internal unity and its ability for decision-making, and in building up key strategic competencies that the other actors cannot ignore.

Scenario 5: Authoritarian International – Syndicate of authoritarian populists

By 2035, a global network of illiberal and autocratic governments will have supplanted the liberal world order and replaced it with an authoritarian-populist power structure. China, Russia and the United States will form the central pillars, supplemented by numerous other states, including European countries under populist governments. Despite their nationalist agendas, these actors are united by a common rejection of liberal principles, pluralistic societies and rules-based international institutions. Foreign policies are highly personalised and de-institutionalised. International relations are based on direct “leader-to-leader” contacts, loyalty networks and situational arrangements.

In terms of security policies, the authoritarian network pursues an active strategy of undermining the remaining liberal democracies. Global security structures have collapsed. International organisations are no longer relevant. Hybrid attacks, economic pressure and selective military force characterise the environment. At the same time, conflicts over territory, resources and spheres of influence are also arising within the authoritarian order. Multilateral conflict resolution mechanisms hardly exist anymore.

Economically, the world order is characterised by corruption, clientelism and national isolationism. Fossil fuel industries are experiencing a renaissance, while environmental and climate protection is losing significance. Innovations are focussed on key security-related technologies such as AI, armaments, robotics and space travel. Renewable energies and environmental technologies are being systematically scaled back. The escalating climate and environmental crisis is being addressed primarily through national adaptation strategies and large-scale technical interventions.

Implications for the EU

The EU is threatened by fragmentation, a loss of innovative strength and the gradual erosion of liberal democratic standards. Supply chains are breaking down and economic and social inequalities are increasing. The EU can counter this by protecting the rule of law, free media and civil society, and by strategically networking with like-minded democracies. In this way, it can build resilience to the autocratisation of the international order.

Scenario 6: Beyond States – A transactional world of non-state actors

By 2035, non-state actors will have gained considerable power. States will continue to exist but will have lost much of their monopoly on the exercise of force as well as their normative authority. The international order will no longer be a state-centred system, but a fluid network of transactional relationships. Multinational corporations, tech billionaires, oligarchs, cartels, megacities, NGOs and social movements pursue their particular interests across borders. Global governance is in a state of constant flux. International organisations and the rules-based order of the 20th century are effectively obsolete.

Security is becoming increasingly privatised. As states have little military capacities of their own, conflicts are being fought out by mercenary troops and private security actors. Economically, companies and cartels are taking over state functions, for example in education, the military and climate adaptation. Global trade structures have collapsed. Alternative currencies and barter systems are widespread. Only a few actors succeed in establishing stable centres where security permits economic activity. In a world characterised by uncertainty, security becomes a key locational advantage.

The climate and environmental crisis is accelerating this development. Regions with stable climatic conditions are becoming sought-after areas for investment and retreat, while other regions are being abandoned as uninhabitable. Adaptation is taking place selectively and exacerbating global inequality.

Implications for the EU

The EU faces considerable risks from the loss of state control, the growing influence of private actors and a possible erosion of values. Particular interests could further undermine democratic structures.

The EU can counter this by protecting the rule of law and strengthening its institutional capacities. This includes promoting its own industrial and technological ecosystem, the consistent protection of data and the targeted regulation of private power.

Four fields of action for the EU applicable to all scenarios

The six scenarios for the global (dis)order in 2035 differ significantly. However, they share one key insight: In none of the conceivable futures can the EU rely on a stable international order or external guarantees for protection. Whether the EU remains capable to act depends primarily on its internal unity, its ability to make quick decisions and its willingness to safeguard its own key interests in economy, technology and security.

Four fields of action can be derived from the scenarios that are relevant regardless of the respective scenario – and that will determine whether the EU can survive as a geopolitical actor in 2035 or whether it will lose influence.

1. Ensuring the capacity to act: faster decision-making, targeted cooperation

If the EU wants to remain capable to act, it should overcome blockages and reach decisions more quickly. Comprehensive treaty reforms remain politically difficult. This makes it all the more important to make targeted use of flexible cooperation formats when formal structures fail.

Minilateral alliances and differentiated integration can open up scope for action – provided they follow clear political guidelines. A shared framework of values and interests is crucial to avoid arbitrariness. At the same time, the EU should expand its strategic partnerships with (like-minded) third countries in order to secure international influence beyond traditional alliances.

2. Making deterrence credible: security as a prerequisite for political action

Without credible defence capabilities, the EU loses its political room for manoeuvre. In all scenarios, security is a basic prerequisite for economic stability and the capacity to act in foreign policies.

The EU should pool its military capabilities more effectively through closer integration of national armed forces, joint procurement and innovation, and better coordinated investment. An effective European defence base strengthens conventional deterrence and increases Europe’s influence – in close coordination with NATO, but with its own capacity to act. Equally important are strong intelligence services, shared situational awareness and a deeper understanding of political dynamics in other regions of the world.

3. Strategically leveraging economic and technological strength

Openness remains one of the EU’s strengths – but without resilience, it becomes a vulnerability. The EU should prioritise those industries, technologies and markets that are crucial to its long-term capacity to act.

A central guiding principle here is strategic indispensability: In certain areas, the EU should create dependencies that strengthen its position. This includes building powerful technological ecosystems, targeting market and technology niches, and creating an innovation-friendly environment that encourages risk-taking. This way, economic strength becomes a geopolitical lever.

4. Securing social support: developing a credible narrative for the future

No strategic realignment can succeed without social acceptance. Reforms, investments and security policy decisions require support – especially in times of transition.

EU institutions and Member States should therefore develop clear, compatible narratives for the future: What do prosperity, security and a good life mean in an uncertain world? Such narratives help contextualise the burdens of reform, bridge transitional phases and provide political orientation. Without this shared narrative for the future, even well-founded measures could lack social acceptance.

Outlook: Capacity to act will determine the future role of the EU

All four fields of action share a common goal: to strengthen Europe’s resilience. In an increasingly volatile international environment, it is more important to focus on the EU’s own capacity to act and react than to prepare for specific future scenarios.

The EU’s ability to shape robust, long-term solutions and defend its interests in 2035 will not be determined by individual policy fields, but by the interaction between governmental, economic and social actors. Key levers – from technological capabilities and the credibility of security policies to education and social cohesion – can only be fully effective through concerted, collective action. Isolated measures will remain ineffective. Only integration, coordination and a shared strategic goal can create actual power to shape the future.

The decisive factor is time. The identified fields of action are not new. What is new is the urgency with which they should be addressed. Whether the EU will be a relevant geopolitical actor by 2035 or lose influence largely depends on consistent, collective and immediate action. An EU that is capable to act, united and internationally compatible cannot be taken for granted – it is the result of political decisions that should be made now.

Methodological explanations

We mapped out the six scenarios for global (dis)order in 2035 and the resulting fields of action in a structured scenario process together with the Fraunhofer Institute for Innovation and Systems Research ISI and German experts from business, academia and politics. The aim was to develop plausible visions of the future that would support political decision-making in times of uncertainty.

This was based on a systematic evaluation of relevant contributions from academia, the media and strategic foresight. Key factors of global order were identified, including power shifts, economic and technological fragmentation, the state of international institutions, security dynamics, and climate and environmental factors. It quickly became apparent that these developments are closely intertwined and cannot be meaningfully considered in isolation.

For this reason, a deductive approach was chosen, in which the scenarios were structured along two key uncertainties:

- the number of power configurations shaping the world order, and

- the degree of their stability.

These two axes make it possible to map the essential differences between possible world orders without creating unnecessary complexity.

Note

This policy brief is based on the detailed report on the scenario process Global Block Formation? Implications of the New World (Dis)Order for Europe: Six Scenarios for International Power Configurations in 2035 , Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh, 2026.

Sources can be found in the PDF version of the study.

Download the Policy Brief

About the authors

Cora Jungbluth is Senior Expert in the Europe’s Future Programme at the Bertelsmann Stiftung. Her research focus is on China, foreign direct investment and international trade, especially the role of emerging economies.

Anika Laudien is Project Manager in the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Europe’s Future Program. She analyzes the changes taking place in China in order to develop recommendations for German and European policy makers.

Write a comment