The new US tariffs are placing significant pressure on Germany and other export-oriented EU economies. In response, the EU is intensifying its efforts to conclude additional trade agreements and to deepen existing ones. However, the expected growth effects remain modest: even under optimistic assumptions, the gains amount to only around 0.6% of EU GDP.

Nevertheless, trade agreements hold strategic importance for the EU. In an increasingly uncertain global environment, they contribute to economic stability and resilience. To sustain progress and avoid political gridlock, the EU could benefit from a pragmatic approach: rather than prioritising large, comprehensive deals that are difficult to finalise, it should first pursue lean but high-impact agreements that can later be expanded and deepened.

Executive Summary

• In light of US tariff policies and growing trade barriers in China, both the EU and partner countries are seeking alternative markets and more reliable trade relationships. This creates both new demands and opportunities for EU trade policy.

• Even under favourable assumptions, new and expanded trade agreements would only provide a moderate growth boost. If the EU were to conclude agreements with 26 additional countries and deepen 40 existing ones, EU GDP could rise by about 0.6% over five years, and German GDP by around 0.7%. The main beneficiaries would be the automotive, electrical equipment and mechanical engineering sectors.

• Diversification and the reduction of strategic dependencies are central priorities for European trade policy in an era of heightened geopolitical tension. New and deeper trade agreements can contribute to this.

• To help achieve these goals, the European Commission should:

• Leverage the current momentum and demonstrate greater flexibility on non-essential issues.

• Prioritise swift agreements of limited scope that can later be expanded through further negotiation.

• Monitor the distribution of gains and costs and mitigate adverse effects, for instance through the Globalisation Adjustment Fund.

• Focus comprehensive partnerships on strengthening resilience and diversification, in combination with targeted investment and complementary policy instruments.

The current US tariff policy is adding to global trade uncertainty. The international trading system has been under strain for some time, as the world’s two largest economies – the US and China – increasingly pursue their geopolitical rivalry through economic means. Smaller, export-oriented economies, meanwhile, remain dependent on reliable and stable trade relationships and are increasingly seeking these within bilateral frameworks. Since the beginning of Donald Trump’s second term, the EU has concluded an agreement with Indonesia and is pressing ahead with negotiations with key partners such as India. Talks are also under way with the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia. This trade agenda has the potential to support moderate growth and greater resilience, but it may also face significant political challenges.

An upper estimate of potential growth effects: three scenarios

Three scenarios illustrate the possible effects under particularly optimistic assumptions. They do not serve as a blueprint for EU trade policy but rather provide an upper estimate of the potential economic impact.

The baseline, or reference, scenario assumes no additional trade agreements and a comparatively moderate US tariff policy – with import duties of 2% on steel, aluminium, and cars, and 30% on all products imported from China. These figures correspond to the average tariff levels set under the US–China agreements in force as of 17 June 2025, when the calculations were made.

Currently (as of 28 October 2025), however, the US has imposed tariffs of 15% on most imports from the EU. The projected growth effects therefore indicate how much higher GDP could be if all the measures assumed in the scenario were implemented immediately and simultaneously.

The first scenario assumes the simultaneous conclusion of new EU free trade agreements with the ASEAN countries (including Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand), India, Australia, the MERCOSUR states (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay), and the eleven ECOWAS countries in West Africa. These agreements are assumed to be “shallow” and relatively straightforward to negotiate, focusing mainly on tariff reductions rather than the comprehensive removal of non-tariff barriers to trade.

The second scenario assumes that the EU will deepen its existing free trade agreements. At present, the EU has trade agreements with 47 countries. This scenario assumes that all these agreements are upgraded to match the level of the EU’s most comprehensive agreements — those with South Korea, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Japan, Singapore and Vietnam. In practical terms, this would mean deepening the agreements with the remaining 40 partner countries.

The third scenario combines the approaches of the first and second scenarios, assuming that the EU both concludes new agreements and deepens existing ones.

The results of the model cannot be directly translated into trade policy realities for three main reasons:

- The scenarios assume that a large number of agreements will be concluded simultaneously. In practice, the pace of negotiations is constrained by technical and administrative factors – such as the capacity of the European Commission’s specialist negotiating teams and those of partner countries, the necessary legal review and translation into all EU official languages, and the ratification process.

- Obstacles remain both within the EU and partner countries. While pressure from US tariffs creates incentives to accelerate negotiations, many trade issues remain politically sensitive. For partner countries, the key concern is often safeguarding policy space, while within the EU, influential member states such as France remain wary of further liberalisation, particularly regarding agricultural imports – as demonstrated by the controversy surrounding the MERCOSUR agreement.

- Trade agreements not only stimulate growth but also enhance legal certainty for firms and strengthen economic resilience through diversification. These effects are not captured by the model but are nonetheless important objectives of EU trade policy and should be factored into any broader assessment of potential benefits.

In reality, the economic effects of new and deeper trade agreements are likely to be smaller and spread over a longer period.

The simulation calculations were carried out using the Kiel Institute Trade Policy Evaluation (KITE) model. The model can estimate these effects over both the short and long term (one year and four to five years, respectively). This reflects the gradual nature of economic adjustments, as free trade agreements typically take time to reach their full impact.

Consequences for Germany and the EU: Moderate growth overall, stronger effects in specific sectors

Scenario 1: The simultaneous conclusion of all new free trade agreements outlined in Scenario 1 would generate a short-term growth impulse of slightly more than 0.2% for the EU – equivalent to around €42 billion relative to 2024 GDP. For Germany, this would translate into a short-term increase in real GDP of just under 0.3%, or approximately €12 billion based on 2024 figures.

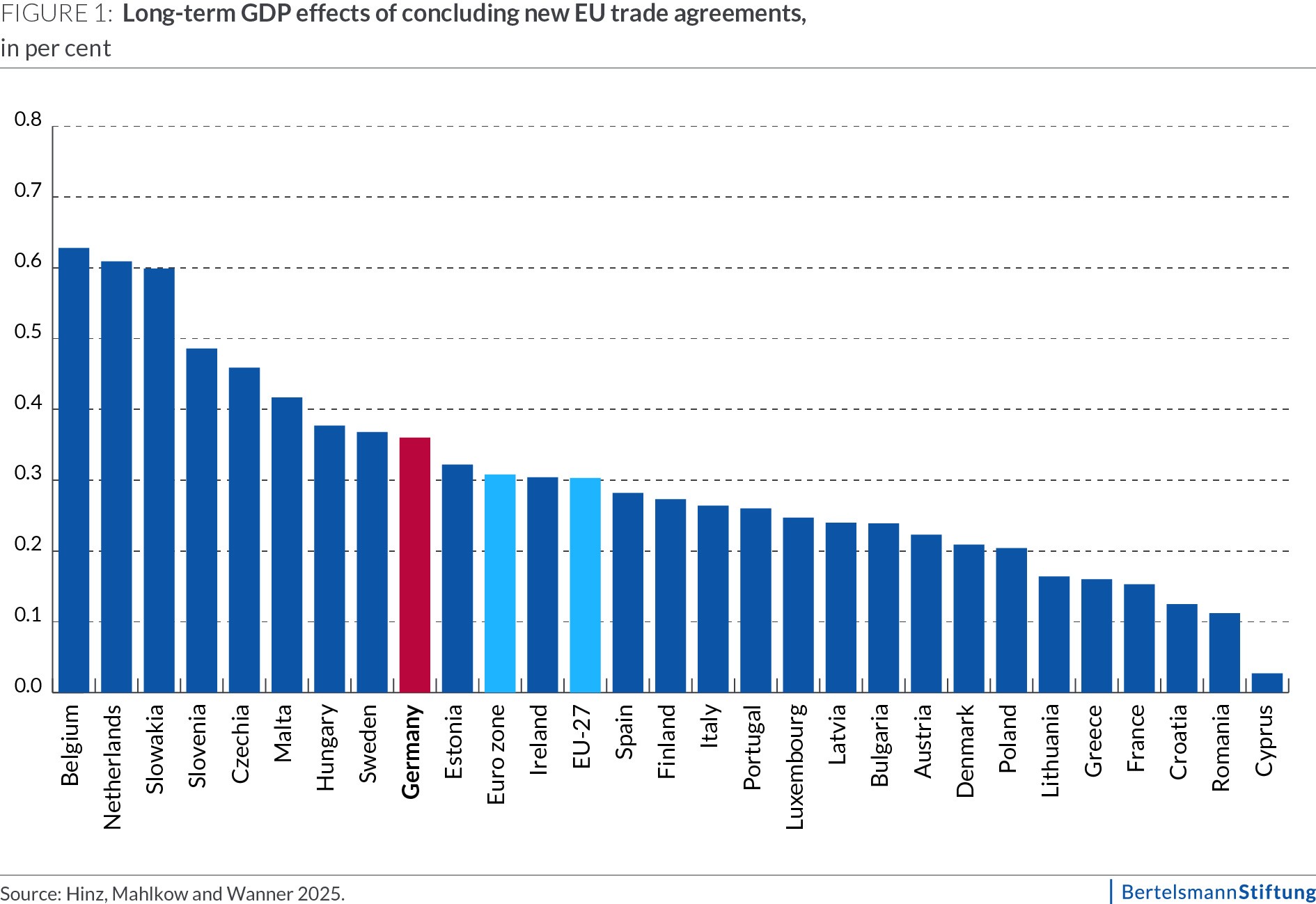

The long-term growth effects of new free trade agreements would be somewhat higher. For the EU, GDP would rise by just under 0.3%, corresponding to slightly more than €54 billion using 2024 GDP as a reference. Germany’s GDP would be 0.36% higher (see Fig. 1), equivalent to around €15.5 billion based on 2024 levels.

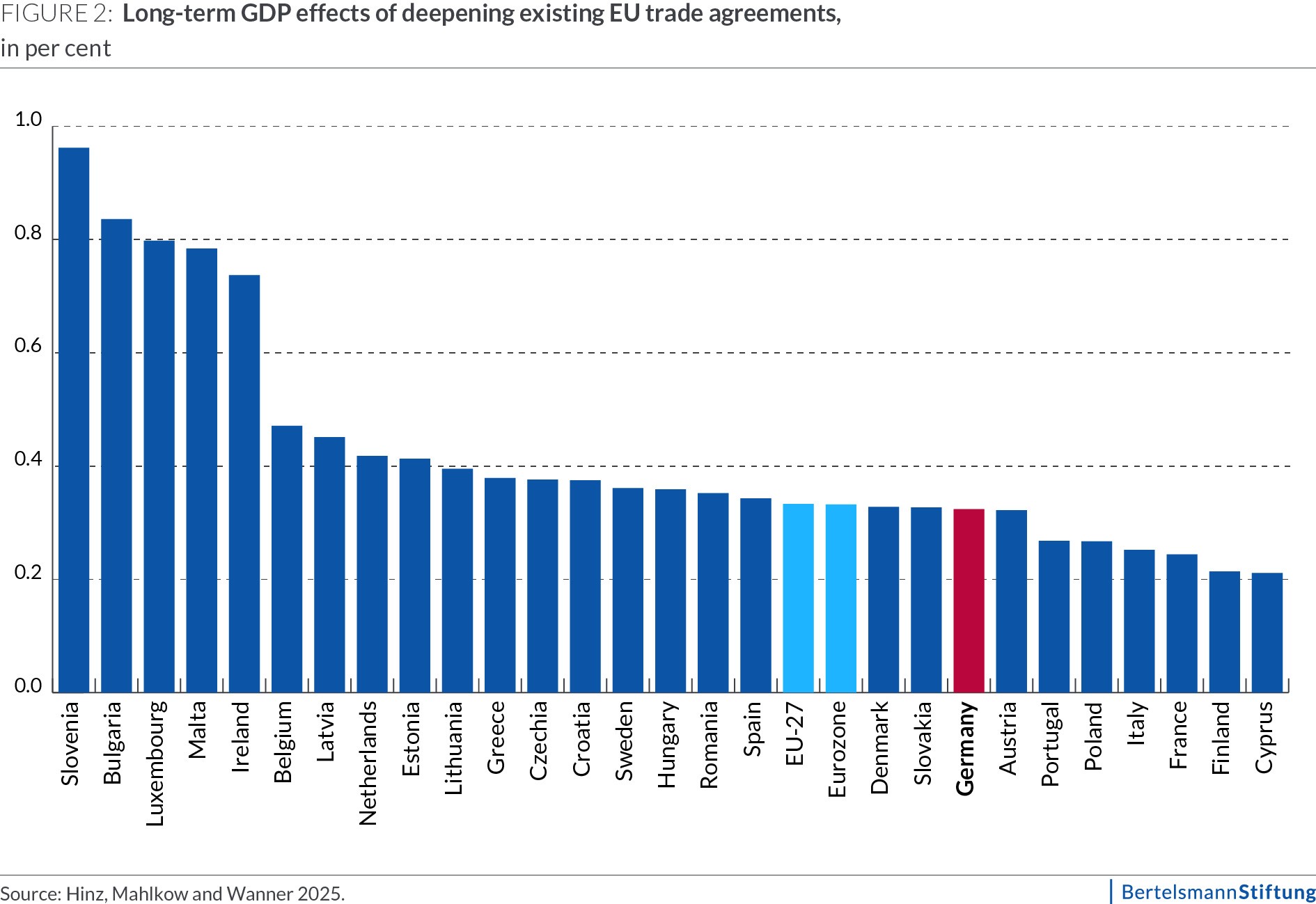

Scenario 2: If the EU were to deepen its existing free trade agreements, the resulting growth gains for the 27 member states would range between 0.2% and just under 1%. Germany, along with other large EU economies such as France and Italy, would record slightly below-average growth in this scenario. In contrast, many smaller EU countries would experience above-average GDP gains (see Fig. 2), as foreign trade plays a proportionally larger role in smaller economies than in those with large domestic markets.

Scenario 3: The combination of concluding new trade agreements and deepening existing ones would produce the strongest overall growth effect. In this scenario, EU GDP would be around 0.55% higher than in the reference case in the short term, and slightly above 0.6% in the long term. Based on 2024 GDP, this would correspond to just over €98 billion and nearly €114 billion, respectively. For Germany, GDP would initially rise by just under 0.6% compared to the baseline scenario – equivalent to around €25 billion in relation to 2024 GDP. In the longer term, the growth impulse would reach slightly below 0.7%, or just over €29 billion.

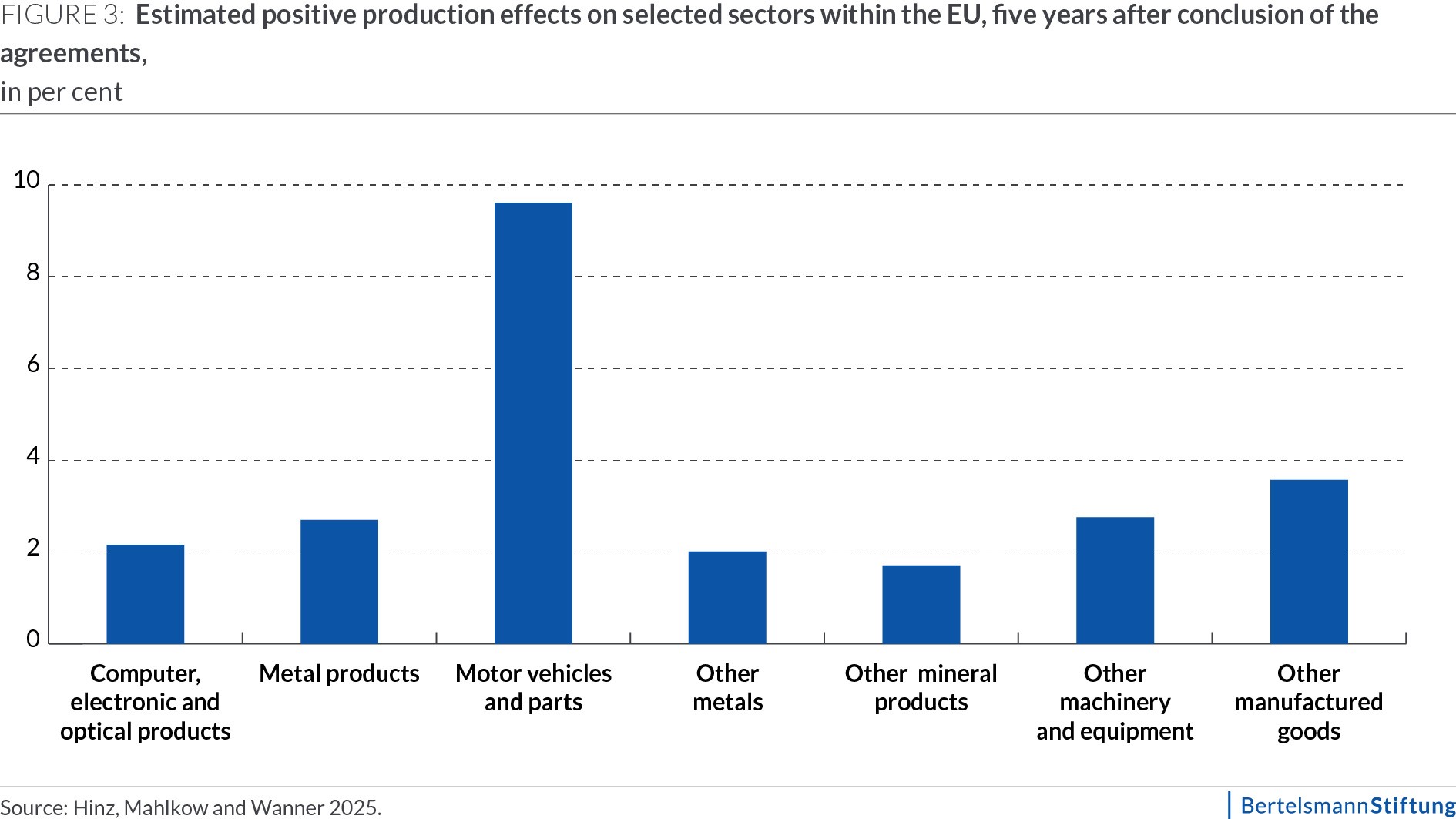

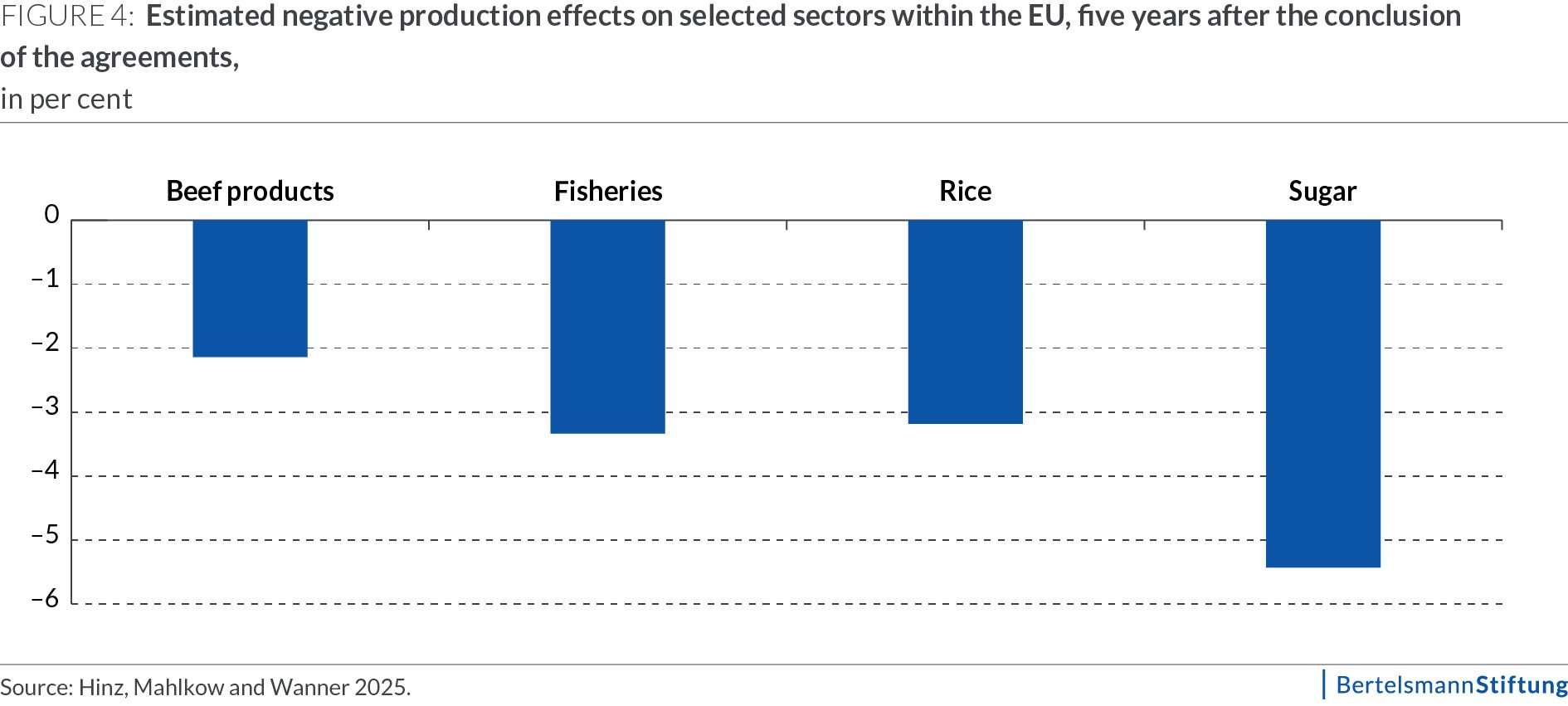

Sectoral effects would vary considerably. The largest positive production effects are expected in the automotive sector – including motor vehicles and parts – with growth of nearly 10%, followed by machinery and metal products. These are industries in which the EU is internationally competitive but also heavily exposed to US tariffs. The expected negative impacts would mainly affect specific agricultural and food products, such as sugar, rice and beef. However, the EU typically shields these sectors through special provisions in its trade agreements.

Consequences for non-EU countries: Modest growth for some, falling prices

Countries entering into free trade agreements with the EU for the first time would benefit from cheaper imports from the EU and, simultaneously, from improved export opportunities to the European market. However, the modelled GDP effects for these countries are smaller than those projected for the EU. This is illustrated by the example of India.

In Scenario 1, India’s GDP is expected to rise by around 0.14% in the short term – a modest figure compared with Germany’s gain of just under 0.3%. The difference reflects the broader scope of benefits for EU member states: while Germany, as part of the EU, would enter new trade relationships with numerous partner countries, India would conclude an agreement only with the 27 EU member states.

Nevertheless, countries newly entering agreements with the EU would gain from cheaper European products. For instance, India’s overall price level is projected to fall by just over 0.4% in the short term under this scenario.

The conclusion and deepening of EU trade agreements would have minor negative economic effects on countries not party to the new arrangements. As the EU strengthens its trade relations with new partners, some diversion of trade away from non-participating countries is likely. Some of the countries affected belong to the group of least developed countries as defined by the United Nations – and many are already among those hardest hit by current US tariff measures.

The deepening of existing EU free trade agreements (Scenario 2) would have varied effects across current partner countries. Some countries can expect noticeable GDP growth. Some would experience notable GDP gains. For example, the short-term growth effect is projected at around 0.6% for the UK, with which the EU already has a trade agreement, and as high as 1.75% for Switzerland. In contrast, Japan and Canada would see no significant impact, as both already have highly comprehensive trade agreements with the EU.

Implications for EU trade policy: Seize the momentum and take a pragmatic approach

Overall, the findings show that even in a hypothetical scenario where the EU were to conclude a large number of trade agreements simultaneously, the growth effects would remain moderate. Strengthening foreign trade can therefore only form one pillar of a broader EU growth strategy – alongside increased investment in future-oriented industries and infrastructure, and further deepening of the single market by removing remaining internal barriers. EU companies will only be able to capitalise on new export opportunities if they are genuinely competitive in the target markets.

Nevertheless, several sectors currently affected by US tariffs – notably the automotive industry – would benefit substantially from broader and deeper trade agreements with alternative partners, helping to offset at least part of the loss in demand from the US. In addition, free trade agreements are an essential instrument for bolstering the EU’s geo-economic resilience and economic security. Against this backdrop, the EU should concentrate on four priorities:

Leveraging the current momentum

In the present global context, the EU is seen by many countries as a stable and reliable trading partner – a reputation that enhances its attractiveness in negotiations. As a result, several partners have become more willing to compromise than in the past. It is therefore timely to restart talks that have long been stalled. Negotiations with Australia, which broke down in 2023 partly over agricultural issues, are also regaining momentum.

The European Commission can best capitalise on this window of opportunity by showing greater flexibility on non-essential issues. For instance, the agreement with Indonesia – unlike other EU trade deals – does not include provisions on investor–state dispute settlement. Member States can also make an important contribution by supporting the negotiation of further agreements politically, both by lending political support to ongoing negotiations and by completing the ratification of already concluded agreements at national level.

Conclude quickly, expand later

A multi-staged negotiation strategy could also prove effective – concluding less comprehensive agreements at first, then broadening them through subsequent rounds of negotiations. Many trading partners, such as India, are eager to strengthen their economic ties with the EU but are discouraged by the scope and complexity of the comprehensive agreements typically proposed by Brussels.

By pursuing simpler initial agreements, the EU can also deepen its trade relations with such partners. In an era of heightened uncertainty in the global trading system, it is more prudent to build trust gradually through achievable, targeted agreements than to delay progress in pursuit of an ideal, but elusive, deal. Later expansion phases could include sector-specific agreements, such as digital trade rules and the mutual recognition of product standards.

Distributing gains and costs

Less comprehensive trade agreements offer greater scope to address domestic concerns, such as fears of increased agricultural imports. Nevertheless, the expansion of foreign trade inevitably has uneven effects across sectors and regions within the EU, with some industries and workers facing adjustment pressures.

To mitigate these effects, the EU and its Member States should work towards a more balanced distribution of the GDP and income gains arising from new and deepened trade agreements. At the EU level, the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund (EGF) remains a key instrument for cushioning adverse impacts, and affected companies should make fuller use of it.

National and local authorities responsible for administering EGF resources can also contribute by improving outreach and communication about the available support. In addition, other economic policy instruments should be deployed, such as the state tax and transfer system, labour market and education policies to support transitions to other sectors, and mobility assistance for workers who need to relocate for employment.

Prioritising partnerships for resilience and diversification

Resilience and diversification, including through the reduction of critical dependencies, should remain clear priorities of EU trade policy, extending beyond purely growth-oriented objectives. This applies both to the choice of negotiating partners and to the design of agreements, for example in areas such as critical raw materials and clean tech value chains.

In these contexts, the EU must strike a careful balance between setting clear, non-discriminatory rules that secure market access for European firms and respecting partner countries’ legitimate policy space for domestic economic development. These partnerships can be successful if the EU presents an attractive, context-specific offer that supports local value creation and aligns with partners’ own development goals.

For critical raw materials in particular, broader strategies are required, as tariff levels and other trade barriers are typically already low. In addition to trade facilitation, this should include investment in transport and energy infrastructure – for example through the Global Gateway initiative – as well as technical cooperation on geological data and support for training systems to develop local skilled workforces.

Model results indicate that several countries of strategic importance to the EU, such as the Republic of Congo, could be negatively affected by new EU agreements with other partners. To avoid straining such important partnerships, the EU should proactively address these spillover effects – for instance, by readjusting unilateral trade preferences in the Generalised Scheme of Preferences and by leveraging development cooperation instruments.

References

Bertelsmann Stiftung (ed.) (2025): “Wachstumseffekte von Freihandelsabkommen für Deutschland und die EU“. Focus Paper # 30 Nachhaltige Soziale Marktwirtschaft. Gütersloh.

Hinz, Julian, Hendrik Mahlkow and Joschka Wanner (2025): The KITE Model Suite: A Quantitative Framework for International Trade Analysis. Bielefeld, Kiel, Vienna, Würzburg.

About the authors

Etienne Höra’s is a project manager focusing on the EU’s foreign economic policy in a geoeconomic age. His areas of expertise include trade policy, economic security and EU-China relations.

Thieß Petersen is a senior advisor specialising in macro-economic studies and economics.

Write a comment