Europe is seeking to elevate its role in space in response to security concerns following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, capability gaps in European armed forces, and uncertainty over U.S. space and alliance policies.

At the same time, space is becoming increasingly commercialised. Europe is encouraging private actors to enter the market, shifting the state’s role from operator to customer. Building robust space capabilities under these conditions requires navigating a set of competing objectives.

Three main tensions define the challenge: sovereignty versus speed, private-sector dynamism versus regulatory ambition, and ecosystem design versus investment preferences. To translate today’s relatively favourable funding environment into durable capability gains, Europe should:

- Adopt a dual-track procurement strategy that reconciles urgent capability needs with long-term industrial sovereignty. This means sourcing from both European and non-European providers in the short term, while accelerating reforms to the European Space Agency’s work-share mechanisms.

- Make commercialisation the main driver of ecosystem growth, expanding challenge-based procurement beyond launch services and ensuring that institutional demand rewards innovation, risk-taking and scalable business models.

- Strengthen and retain Europe’s industrial base through targeted ‘buy European’ policies, selective consolidation where necessary, and new financial instruments – such as a Strategic Space Fund – to keep competitive firms and talent anchored in Europe.

Introduction

Space assets are now central to both economic performance (European Commission 2025b) and security and defence purposes (Süß 2025). Yet Europe faces significant dependencies on the United States in this sector, including situation awareness in space, launch

services, military space assets, satellite components and crewed spaceflight.

Against the backdrop of a shifting transatlantic relationship and a more hostile security environment in Europe, strengthening Europe’s existing space capabilities and industrial base has become a prerequisite for greater autonomy and strategic resilience. Paradoxical-

ly, however, the sector’s most dynamic and innovative developments are now emerging from the private sector – enabled by policies explicitly designed to promote commercialisation.

Political Changes Meet Commercialisation Trends

The space sector is changing, and this change is mostly driven by two trends: First, the renewed importance of state institutional demand, primarily for security and defence purposes. Second, a changing space industrial ecosystem that could, in future, thrive on commercial demand – provided policy frameworks actively support this reconfiguration.

Political Ambitions and Investments

Security concerns in Europe are intensifying, due to the threat of a militarily reconstituting Russia as well as the Trump administration’s ambiguous space and alliance policies that lay bare space capability gaps in Europe’s armed forces. Counteracting enduring dependency on U.S. space capabilities is no small feat (Süß 2025), but Europe is beginning to respond.

In line with the established division of labour across Europe’s distributed space sector, national security and defence programmes are currently at the forefront of this activity. Poland, for example, is investing in Earth observation capabilities (Adamowski 2025; Gwadera 2025). Germany’s defence minister, Boris Pistorius, has announced planned investments of €35 billion into defence-related space capabilities (Bundesministerium der Verteidigung 2025), while France has also increased planned investments (Desmarais

2025), to name but a few examples. Both France and Germany have recently published new space (security) strategies (Republique Francaise 2025; Die Bundesregierung, 2025).

At the same time, activity is increasing at the multi- and supranational levels. The European Space Agency (ESA) has announced higher spending over the next three years, alongside more ambitious planning for this period (European Space Agency 2025a), while widening its mandate to include security and defence (Kayali 2025). In Brussels, meanwhile, the European Commission’s draft Space Act is being debated intensively, with input from industry, member states and allied partners (European Commission 2025a). While these institutional actors continue to shape Europe’s space ecosystem, a shift towards greater commercialisation is already under way (Johns Hopkins University 2025). If deployed effectively, rising state investment in Europe could be used to support and accelerate this transition.

Commercialisation Trends

Commercial actors dominate media coverage and the broader news cycle about space – from the landing of reuseable rocket boosters (Tribou 2025) to private actors checking off milestone achievements such as spacewalks (Rannard 2024). This commercialisation of

the space ecosystem is arguably the most significant overarching trend in the industry and is widely expected to bring about transformative change (Schütz 2020).

Fundamentally, though, commercialisation in space is nothing new. Certain segments – most notably communications and satellite manufacturing – have been commercialised for decades, with private commercial demand long outstripping institutional and state demand by a wide margin (e.g. Eurospace 2025). Commercial launch companies, though all failing in their time, already existed as early as the 1970s (Rösing 2025) and into the 1990s (Heyman 2013). Three of today’s most prominent private launch companies, SpaceX, Blue Origin and Rocket Lab, were all founded in the early 2000s (O’Connor and Curlee 2025).

To date, however, comprehensive commercialisation encompassing the entire space sector – and fundamentally reshaping supply, demand and innovation processes – has not occurred. State-led institutional demand remains critical to the viability of the overall ecosystem (Veugelers et al. 2025). Where meaningful progress in commercialisation has taken place, particularly in the United States, it has largely been driven by changes in NASA’s procurement and contracting practices. Over the past 15 years, these have increasingly shifted towards a ‘space as a service’ model (Schütz 2020).

Through this shift, institutional actors no longer as sume responsibility for operating spacecraft once they have been manufactured and delivered by private firms. Instead, they purchase services – for example, transporting cargo or astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) (NASA, n.d.-b). This model gives companies greater freedom in meeting the technological and financial requirements set by public clients and helps decouple programmes – traditionally shaped by pork-barrel politics – from some of the distortions associated with highly politicised markets.

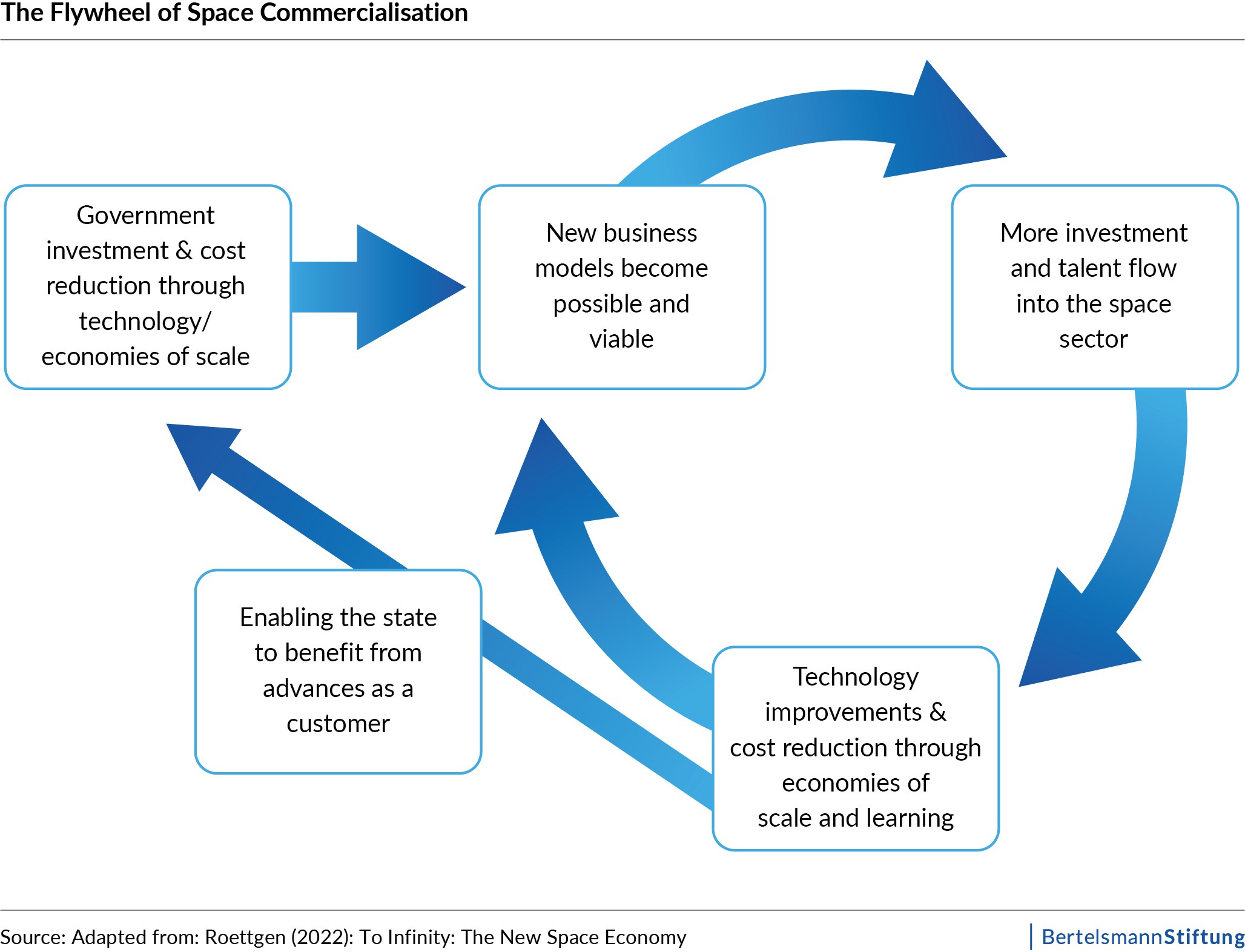

Through the adoption of ‘space as a service’, state actors aim to foster deep commercialisation of the space ecosystem by shifting investment, demand and innovation increasingly towards the private sector, as illustrated in Figure 1 (Roettgen 2024). In this model, initial state demand creates the conditions for products and services to mature technologically, enabling commercial applications that, in turn, generate further innovation and private-sector engagement.

‘New space’ – the colloquial umbrella term for emerging business models that may underpin this evolving commercial ecosystem – encompasses a wide range of activities. These include established services such as satellite data for Earth observation, as well as manufacturing processes in microgravity and more speculative applications, including asteroid mining (Grest 2020).

Notably, this predominantly U.S.-driven narrative of commercial ‘new space’ has gained traction well beyond the United States, including in Europe. In pursuing commercialisation, many space actors therefore look to the U.S. experience as a model to emulate.

Yet the developments observed in the United States were enabled by a specific combination of national and cultural factors, including, first, a widespread perception of intense geopolitical competition with peer or near-peer rivals in a domain of high national security relevance; second, a corresponding level of demand from the U.S. national security apparatus – including the armed forces and intelligence services – with a strong emphasis on technological superiority; third, a cultural preference for limiting the role of government in delivering solutions to these challenges (Weiss 2014); and fourth, institutional and industrial experience drawn from other technology sectors, such as microchips, and applied to space (Schütz 2020).

Another core tenet of the U.S. approach to space commercialisation is assuring redundancy and a minimum of two suppliers for critical functions – from launch services to satellite manufacturing and human lunar landings (e.g. Mohon 2024). This principle is particularly important in a technologically demanding field such as space, where delays have affected almost every major programme, ranging from human spaceflight (Rou lette 2025) to the introduction of new launch vehicles.

Conflicting Policy Goals

As Europe plans to increase space-related spending – raising annual expenditures by at least 50% over the coming years compared with, for example, 2022 levels (see Renčelj 2024) – and has largely embraced the U.S. narrative on space commercialisation, it is better positioned to begin activating the flywheel of space commercialisation than it was only a few years ago. Yet a clear strategy for translating this narrative into a concrete vision – one that balances competing policy objectives and reflects Europe’s distinct institutional and industrial context – remains absent. This gap is becoming increasingly problematic given the compressed timelines associated with defence-driven capability requirements, which account for a substantial share of the planned increase in investment over the coming years.

Sovereignty versus Time

Security pressures are acute, and non-European industrial suppliers may be better positioned to deliver hardware and services at speed. Yet the systematic build-up of industrial capabilities and capacities required to strengthen Europe’s autonomy in space inevitably takes time – regardless of the level of funding being applied.

By now, senior European politicians, military officials and intelligence representatives have set out stark timelines regarding the threat posed by Russia in the coming years. The late 2020s are widely viewed as a point at which Russia could be capable of attacking additional European countries beyond Ukraine. If Europe – as a limited space power (Aliberti 2023) – seeks to enhance its military capabilities while simultaneously increasing defence sovereignty, it will require a broader portfolio of space assets. These span intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; positioning, navigation and timing; missile early warning and tracking; and communications (Süß 2025).

If rising institutional demand – particularly in security and defence – becomes the primary driver of Europe’s space ecosystem over the coming years, a clear dilemma emerges. Capabilities must be deployed rapidly to strengthen Europe’s deterrence and defence posture, yet domestic industrial capacity and capability may be insufficient to support an exclusively European procurement strategy. This creates incentives to contract suppliers from outside Europe, notably the United States (Erwin 2025b). Even where European suppliers are available, traditionally risk-averse defence procurement agencies may favour established firms over new market entrants offering unproven technologies. In addition, long production lead times and pre-booked launch slots require planning horizons of several years (Daehnick et al. 2023).

In the German context, for example, annual spending of roughly €5 billion would require industrial capacity to double or more (European Space Policy Institute 2025a), a scale-up that seems unrealistic despite industry assurances. This problem can be mitigated by directing as much investment as possible towards European companies. Even so, multiple bottlenecks – ranging from physical infrastructure and workforce recruitment to skills development, production processes, supply chains and their synchronisation – limit the ease with which capacity can be expanded. Already, large parts of Europe’s space industry face significant talent shortages, particularly in areas such as software and data, electronics design and systems engineering (Copernicus 2025). Additionally, Europe does not make optimal use of the talent it possesses. Barriers to sector entry, competition with other high-technology industries, and weak development pathways for graduates and early-career professionals all constrain workforce growth (European Space Policy Institute 2025b). For certain segments of the space ecosystem, this will continue to necessitate international procurement. Launch services, in particular, stand out due to the limited number of European launchers and constrained availability in the foreseeable future (Greenacre 2024) – even if European start-ups succeed in reaching orbit in the near term. Both transatlantic cooperation and partnerships with launch providers in like-minded countries such as Japan or New Zealand may offer partial relief. Against this backdrop, clear and upfront communication is essential. Explicitly prioritising the rapid delivery of equipment and services to European armed forces and intelligence agencies over near-term capability-building can help prevent disillusionment within the space sector, which has traditionally operated on longer development timelines.

Private-Sector Dynamism versus Regulatory

Ambition

There are different pathways towards greater Europe- an sovereignty and autonomy in space, yet no shared European consensus on which route to pursue. Germany and the ESA, for example, have placed increasing emphasis on nurturing a nascent start-up ecosystem through U.S.-style commercialisation approaches. France, by contrast, continues to prioritise established industrial actors and their proven capabilities. At the same time, the European Union is seeking to shape and regulate the sector in order to improve the safety and sustainability of space activities, while facing strong resistance from member states, industry and international partners concerned about perceived overregulation and regulatory overreach.

European efforts to emulate U.S. commercialisation models are most visible in launch policy. At the national level, Germany’s Microlauncher Competition, launched in 2020 (Burkhardt, n.d.) supported promising start-ups with the explicit aim of funding innovative concepts that could enable cheaper access to space (Mittelbach 2020). At the European level, ESA’s Launch Challenge – established in 2023 and preceded by the Boost! Initiative (European Space Agency, n.d.) – marked an important milestone by selecting five start-ups to deliver indigenous launch systems for the small and medium launch market. In parallel, ESA’s Flight Ticket Initiative, implemented in cooperation with the EU, places a strong emphasis on the role of public institutions as anchor customers for emerging launch providers (Parsonson 2025b).

The stated objectives of these initiatives underline ESA’s ambition to follow the U.S. model of launch commercialisation: fostering competition among European launch providers, promoting a diverse access- to-space ecosystem, supporting the development of innovative and cost-effective launch solutions, and enhancing Europe’s autonomy in space transportation (European Space Agency 2025b). The selected companies and their launch vehicles are expected to achieve orbital launches by no later than 2027, with ESA missions planned between 2027 and 2030 and mission requirements set to expand over time (European Space Agency 2025b). In this respect, Europe’s approach closely mirrors NASA’s commercialisation strategy over the past 15 years (Schütz 2020). At the heavy-lift end of the launch market, though, European competition remains distant. The Ariane 6 launcher is set to remain Europe’s only heavy launch vehicle until start-ups accumulate sufficient technical experience and financial resources to enter this market segment.

For satellites and other spacecraft, the EU Commis sion’s Space Shield might offer an opportunity to strengthen non-traditional suppliers as the EU appears generally willing to use public procurement strategically to support the development of new space tech- nologies (Pesonen 2022). In this context, start-ups, micro- and mini-launcher firms, and other ‘new space’ providers could benefit from institutional demand generated by Space Shield and related programmes.

On the regulatory front, stakeholders broadly support the objectives of the European Commission’s draft Space Act, particularly its focus on safety, sustainability and the functioning of the single market. At the same time, many warn that the draft’s broad scope, legal ambiguities, compliance burden and potential discriminatory effects could raise costs, dampen innovation and fragment international cooperation (Bundesverband der Luft- und Raumfahrtindustrie 2025). Additional reporting requirements, technical standards and insurance obligations could increase operational and compliance costs for commercial op- erators, especially small and medium-sized enterprises. Lengthier authorisation and assessment procedures risk slowing market entry and product development cycles, while new rules on debris mitigation, cybersecurity and data handling could require costly design or operational adjustments. For non-EU firms, the draft’s expansive reach creates uncertainty over market access and may necessitate global compliance changes (Office of Space Commerce 2025). Overall, legal ambiguities in the proposal increase regulatory risk, com- plicating long-term planning for all commercial actors. This stands in contrast to the U.S.-led Artemis Accords, which 27 European states – from Iceland to Ukraine and from Finland to Spain – have joined. The Accords seek to establish principles governing the exploration and use of outer space, particularly in the inner solar system, with a comparatively commercial-friendly orientation (NASA, n.d.-a).

Ecosystem Configuration versus Investment

Preferences

Europe currently finds itself between two stages: an initial phase of increased state-led investment and state-funded technological development, and the emergence of new business models capable of attracting private capital and talent. If state-led investments over the coming years deliver sufficient technological progress, some of today’s unfavourable trends could be reversed. At present, however, demand signals point in the opposite direction. While overall sales in the European space industry have stagnated at around €8.5 billion over the past decade, the commercial share of those revenues – including exports – has declined. Institutional demand has therefore grown in relative importance, with commercial sales accounting for only around a quarter of total revenues in 2024 (Eurospace 2025). In the early 2010s, sales were still split almost evenly between commercial and institutional customers.

This shift largely reflects structural changes in the market. Europe’s traditional industrial strengths – namely highly complex, high-quality large satellites for geostationary orbit – have lost relevance as communications traffic has become increasingly digital and as satellite constellations and associated capabilities have proliferated in low Earth orbit (European Space Policy Institute 2025). With security- and defence-related demand now taking the lead (Erwin 2025a), and with continued improvements in the technical performance of smaller satellites – alongside their greater resilience when deployed in constellations rather than as single platforms – these trends are likely to intensify further in the coming years. State demand should therefore incentivise incumbent firms to redirect internal development efforts, both in terms of space assets towards smaller satellites and, more importantly, in production processes away from bespoke manufacturing and towards mass production. At the same time, established commercial success for launch services from Ariane- space suffered from delays in the introduction of the Ariane 6 launcher, losing market share to SpaceX in particular (Triezenberg et al. 2024).

Additionally, most European space companies continue to generate a substantial share of their revenues within Europe and from European customers (Euro- space 2025). Relying on exports as a solution is thus not tenable. At the same time, the emergence of new suppliers increases global competition across the value chain. Institutional demand will thus need to strike a careful balance between reinforcing the tradition al strengths of established suppliers and supporting emerging firms with technological potential that is better aligned with prevailing economic trends in the space sector.

This challenge feeds directly into the broader question of whether a genuinely commercial European space industry is viable, and it underscores the need for targeted policy interventions to steer the ecosystem in that direction. Even in the United States – where national security demand is far greater than in Europe, and where SpaceX has captured large portions of the globally contestable heavy-launch market – questions persist over whether demand is sufficient to sustain more than one heavy-launch provider, or whether substantial internal demand, such as SpaceX’s Starlink programme, is a prerequisite for commercial viability (Triezenberg et al. 2024). While European small and medium launch providers may initially carve out niches by supplying launch services to European armed forces, entry into the global heavy-launch market will face significantly higher barriers. A similar adjustment challenge confronts Europe’s satellite manufacturers, as demand increasingly shifts towards low Earth orbit constellations.

Consequently, purely competition-driven, open-market policy approaches are unlikely, for the time being, to deliver the degree of commercialisation European governments are seeking. To avoid monopolistic out comes with price-setting power, Europe should consider adopting the U.S. approach of maintaining and supporting a minimum of two suppliers in critical segments, even where this entails higher per-unit costs, particularly for launch services. In other areas of the space industry, the risk may be less acute, although further consolidation among large legacy players could nonetheless prove problematic in this regard (Parson- son 2025a).

Finally, the United States shows little sign of revising its approach to space commercialisation and is likely to continue leveraging its first-mover advantage (The White House 2025). In fact, with a greater focus on China as a geopolitical competitor in space (Nelson et al. 2025), rising defence-related space spending – in cluding for the U.S. Space Force and programmes such as Golden Dome (Bowen 2025) – and the continued maturation of private space firms (Swope 2025), transatlantic competition in the space domain will intensify.

A European Way Forward

Commercialisation holds the promise of transformative change in the space sector. With rising levels of investment, Europe can now begin activating this dynamic in earnest. Simply replicating the U.S. approach, however, is unlikely to succeed – both for economic and political reasons. Europe will therefore need to chart a similar, but adapted, path. Three steps are particularly important:

- Given the favourable funding environment and outlook, European states should pursue a dual-track approach in which national or European solutions are developed in parallel with the procurement of launches, equipment and services from non-European suppliers. Compared with other areas of defence spending, overall expenditure in the space domain remains relatively modest, making such a dual-sourcing strategy feasible. This approach can help reconcile urgent time pressures with the longer-term development of domestic capabilities, even if initial investments fall short of the scale desired by European industrial players. For ESA and the EU, which already place a stronger emphasis on European procurement—for example through ESA’s work-share arrangements—this tension is less pronounced. Nonetheless, ESA’s work-share system could benefit from reform, shifting towards a model that balances industrial shares across its expanding portfolio of projects rather than within individual projects, akin to the Organisation Conjointe de Coopération en Matière d’Armement’s (OCCAR) global share concept (OC- CAR, n.d.).

- Commercialisation is Europe’s most promising route to expanding its space ecosystem (Veugelers et al. 2025), a view broadly shared by the European Commission (European Commission 2025b). The U.S. practice of soliciting private-sector solutions through challenge-based procurement – most visibly through ESA’s Launcher Challenge – has demonstrated its relevance in the European context as well, given Europe’s strong aerospace talent base and maturing start-up ecosystem. While the current lack of challenges beyond launch services and low Earth orbit cargo transport may appear unambitious, it reflects a focus on those industry segments with the greatest commercial potential at present. These include both legacy demand for launch and emerging activities such as microgravity manufacturing, where related Earth-based industries are long-standing European strengths. Member states, and the European Commission in particular, should therefore concentrate regulatory efforts on enabling these activities, while steering institutional demand towards greater openness and a higher tolerance for risk (Veugelers et al. 2025).

- Nurturing Europe’s space ecosystem will require a deliberate commitment to ‘buy European’ wher ever feasible. Without such an approach, the first-mover advantages already secured by U.S. firms – particularly in launch and reinforced by the maturation of additional launch systems in the coming years – risk undermining long-term industrial security and planning certainty in Europe. At the same time, both the European Commission and member states will need to articulate a clearer vision for the sector, one that reconciles Europe’s limited market size with a realistically scaled competitive landscape. This is likely to entail consolidation or the exit of some firms (Veugelers et al. 2025) and will need to be more specific than the Commission’s current broad strategic framework (European Commission 2025c). At the same time, retaining innovative companies in Europe will also require sustained access to both public and private capital. For the EU, this could take the form of government-sponsored venture capital (GVC) within a Strategic Space Fund, as recommended by the European Space Policy Institute (European Space Policy Institute 2025a). The financial commitment for such a GVC can be modest: even In-Q-Tel, the well-known CIA-backed government venture capital vehicle, which invests across four areas – space, energy, microchips and biotechnology – deploys only around €100–150 million annually (ProPubli- ca, n.d.). ESA, particularly in light of its expanded remit to include resilience, could oversee such a fund as a non-profit entity. Its three-year budget cycles would offer both investment stability and sufficient time for portfolio companies to deliver initial results, while ministerial meetings could be used to define overarching investment priorities. This would allow for a more direct investment control and direction than current instruments like CASSINI (European Commission, n.d.).

Sources can be found in the PDF version.

Download the Policy Brief

About the author

Torben Schütz is Senior Expert in the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Europe Programme.

Write a comment