The European Commission has made rapid simplification of EU rules key to its competitiveness strategy. It has put forward six Omnibus packages designed to revise multiple legal acts at once. Yet, instead of making rules clearer and more workable for companies, parts of its agenda weaken standards — thereby missing the very purpose of simplification: reducing costs while preserving those standards. Moreover, only a few proposals have been adopted by the EU Council and the European Parliament (EP), while others remain stuck in political deadlock.

To deliver effective simplification, the Commission should recalibrate its approach and adhere to four principles:

- Clarity on goals: simplification should not be deregulation in disguise

- Evidence-based selection: focus on rules that create high costs with little benefit

- Sound design: use Better Regulation tools to design simplification proposals

- Foster political consensus: align early with Council and European Parliament on goals and scope to avoid deadlock

This way, simplification will reduce costs, safeguard standards and strengthen competitiveness.

Bureaucracy is a major burden for European businesses and especially SMEs. 61% of firms – and 63% of SMEs – report that the regulatory environment is an investment barrier. A recent study commissioned by the European Parliament (EP) adds that SMEs are particularly concerned about the introduction of many new EU rules on the digital and green transition and about a trickle-down effect that impacts them even when they are exempt from regulations. The issues with EU law stem also from how it is made: legislation developed in silos across DGs, ambiguous legal language, and a lack of implementation guidance taken together create inconsistencies, duplications, and higher administrative costs.

The question is not whether to simplify, but how. Simplification is not an end in itself – it is an instrument to make Europe’s regulatory standards work more effectively for companies and to support competitiveness. To achieve this, simplification needs to be done right.

The Commission has rightly put simplification high on the agenda. So far, however, the Omnibus packages have struggled to deliver on their promise of effective and rapid simplification. Despite an overarching simplification strategy, the rationale for which laws are included in the Omnibus proposals is not always clear. Even some recently adopted legal acts are under review, although implementation experience is inevitably very limited. Furthermore, several proposals appear to have been developed with scant evidence. Instead of streamlining and improving rules, some proposed changes could increase compliance costs by adding new layers of red tape. At the same time, the Commission has shown that it can learn from earlier criticism, for example by consulting more actively on which laws should be simplified.

The Omnibus agenda also runs into a divided political centre. Conservatives and right-wing political groups see it as a chance to reverse legislation under the Green Deal. They have repeatedly pushed for far-reaching changes or called for the abolition of certain rules. Socialists and Greens on the other hand, have criticised the agenda, fearing a roll-back of hard-won policies. Trust is low as each side suspects the other of not being genuine in their willingness to simplify. This environment makes it essential for proposals to be clear and targeted.

To achieve simplification that rapidly and tangibly reduces red tape for companies and boosts EU competitiveness, the Commission should follow the four principles laid down above. These principles directly address some of the weaknesses of the current Omnibus agenda: blurred objectives, rushed design, and political deadlock. By applying these principles, the Commission can deliver what businesses actually need: better rules that cut costs while upholding Europe’s high standards.

The Commission’s Omnibus agenda

In his report, former ECB President Mario Draghi identified simplification as an urgent area for EU action: Europe should streamline its regulations to better leverage its high standards for attracting investment and promoting innovation.

Following Draghi’s recommendation and under increasing pressure by member states and business associations, the Commission published its simplification communication in spring 2025. Its aim is to reduce recurring administrative costs borne by EU companies by €37.5 billion, from an estimated €150bn (roughly 0.9% of EU GDP, Eurostat approximations in 2022 numbers). This would amount to a 25% reduction in administrative costs for large companies. For SMEs, the Commission seeks to reduce costs by 35%.

The Commission’s long-term strategy is ambitious: Over the next five years, it plans to “stress test” the entire EU rulebook for simplification potential and to conduct “reality checks” with companies. New rules will undergo reinforced scrutiny for simple language and their likely effects on SMEs. The Commission also aims to strengthen collaboration with co-legislators on prioritising simplification measures and to support member states in implementation of rules in national law. These plans are ambitious and, while they will take time to show results, they have the potential to deliver noticeably lower administrative costs in the medium to long term.

For more immediate relief of administrative burdens, the Commission is moving ahead with ‘Omnibus’ proposals – legislative packages that propose to change multiple regulations or directives at once.

The first two of these six proposals, focusing on sustainability legislation and the InvestEU Programme, were set out in February 2025. They were followed by proposals on agriculture, a definition for small mid-cap firms, defence and chemicals.

The agenda has been met with challenges and has produced mixed results. So far few of the proposals have been adopted and the programme has deepened divisions between political groups in the EP. The attempt to simplify the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive illustrates these difficulties.

Lessons from the CSRD

The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) was established to standardise sustainability reporting for large companies, improving transparency for investors and firms managing sustainability risks. It provides coherent and comparable disclosures – for example on greenhouse gas emissions, workforce, or business conduct – to inform sustainable investment practices.

The directive and especially its reporting standards have drawn criticism for being too burdensome and overly complex, particularly from business associations.

The Commission took the criticism seriously. As part of the first Omnibus package, it proposed to delay reporting, reduce the number of companies in scope by 80%, cut the number of data points and limit information requests from business partners. However, the Commission’s proposal revealed both technical and political challenges.

First, the proposal would in effect prevent the directive from achieving its intended impact. The changes, especially on scope, would significantly reduce access to sustainability-related information in the EU and thereby threaten an efficient allocation of capital towards firms that are well-aware of and prepared for climate-related risks. Furthermore, it would slow down the transformation of business models. Investors and standard setters warned of weakened competitiveness, while business associations welcomed lighter reporting obligations.

Second, in its drive to act quickly, the Commission skipped standard steps in the legislative process: A staff working document replaced the impact assessment bypassing normal scrutiny. Instead of broad stakeholder consultation, invitation-only closed-door sessions took place. To expedite the discussions on the proposal, the Council created a special group, side-lining technical experts. This approach drew criticism from civil society and diplomats alike, and triggered an investigation by the EU Ombudsperson.

The fast pace of design impaired the quality of the proposal. Instead of aligning with other instruments or improving guidance, the Commission simply cut the number of companies in scope. Certain changes – especially the restrictions on requesting information from business partners in the value chain – might increase compliance costs instead of reducing them. A more measured approach, such as simplified standards for small mid-cap companies or clearer guidance, could have eased costs without weakening the directive’s core objective.

Finally, the Commission did not secure a political majority in the EP and Council for rapid adoption. The Council largely endorsed the Commission’s proposal, but the EP remains divided, with hundreds of amendments delaying the adoption and creating considerable legal uncertainty for companies.

This example shows how not to simplify – and this lesson reaches beyond this single directive. Simplification cannot succeed when objectives are blurred, proposals are designed in a rush, and political support is missing. As the Commission will continually review the entire body of EU law, more Omnibus initiatives are to be expected. Unless lessons are learned from this example, future packages will repeat the same mistakes. The next sections explain how to simplify – starting with clarity on goals.

How to rapidly and effectively simplify

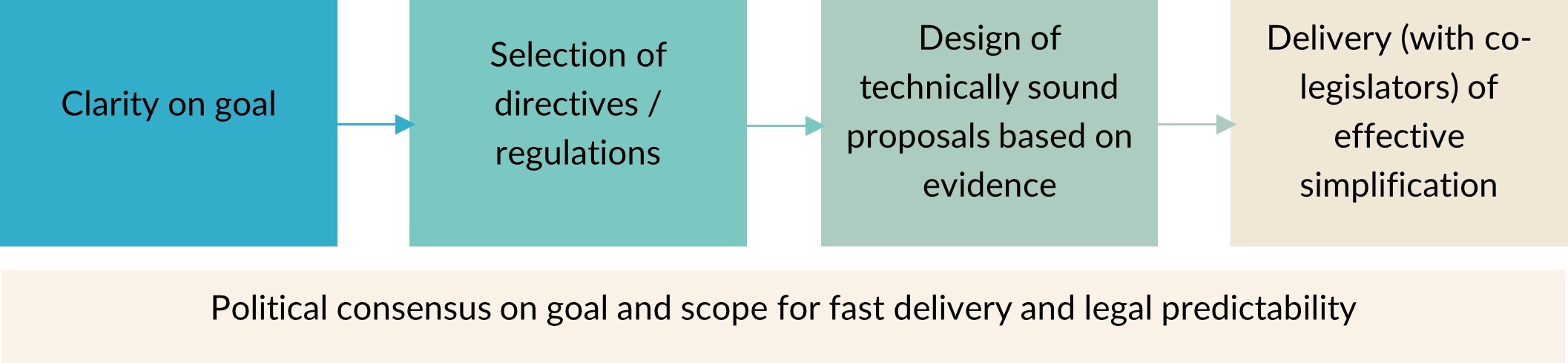

Fast and effective simplification requires clarity on goals, technically viable proposals and a majority in the Council and EP (see Figure 1). This section introduces the necessary steps towards a successful simplification agenda.

Figure 1: Steps towards effective simplification

1. Clarity on goal: Simplification vs. deregulation

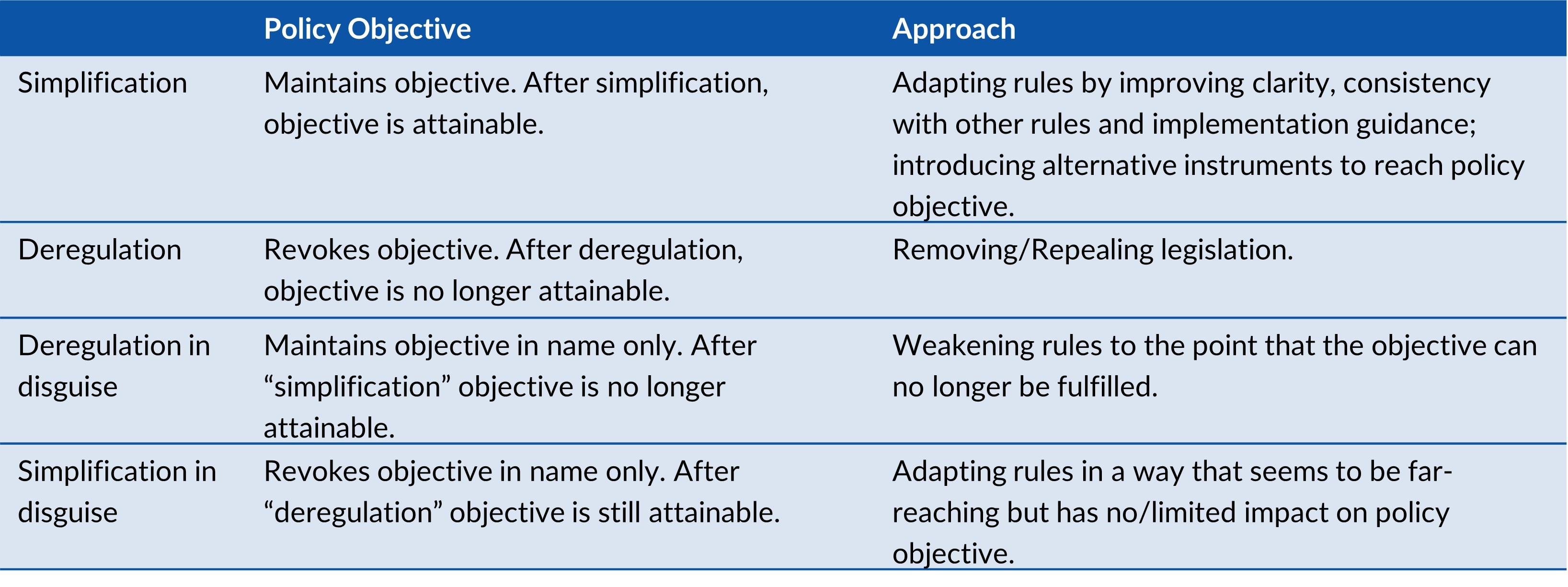

Effective simplification starts by understanding the difference between simplification and deregulation. Simplification preserves policy goals and makes rules and their implementation more effective, coherent, and efficient – for example, by streamlining legislation or improving clarity. Done well, it can enhance competitiveness while protecting one of Europe’s strengths: its high standards, a robust regulatory framework, and the ambition to reach net zero.

Deregulation, by contrast, reduces or removes the underlying policy objective. It can be a legitimate policy choice, but when it is used to dismantle standards that are predicted to support long-term competitiveness in favour of short-term gains, it can weaken Europe’s strength.

Two hybrid forms often appear in political communication. The first is “deregulation in disguise”: changes labelled as simplification that weaken policy instruments until they become ineffective. The second is “simplification in disguise” where the policy objective is officially revoked, however the changes to the law have limited impact on it. Table 1 sets out the differences.

Clarity also matters at the level of instruments at which simplification or deregulation takes place. For example, car emission standards were introduced to cut emissions from private vehicles. Removing them would be deregulation at the instrument level, even if the overarching objective of reaching net zero still stays formally intact. True simplification of the emission standards would mean streamlining the standards with other rules or reducing complexity while keeping the goal intact.

This framing, often used in policy debates, shows why clarity on goals and instruments is essential – and how language can blur these distinctions.

Table 1: Differences between simplification, deregulation, deregulation in disguise and simplification in disguise

2. Selection of rules: Identifying what to simplify and why

High standards can drive innovation and investment, but only if they deliver the intended impact and remain workable for companies. Some EU rules, however, are inconsistent and too complex, imposing costs without added value. Effective simplification therefore requires a strategic selection process: Which rules require simplification, and why?

That task is not straightforward. Significant data gaps exist: there is little evidence on how individual laws impact companies or the wider economy, as evaluations and impact assessments usually provide only rough pre-implementation cost estimates. This lack of data complicates targeting simplification where it could both cut unnecessary costs and strengthen the competitiveness of the EU’s legal framework.

While selecting laws to simplify, two principles should apply:

- First, the choice should be policy-area agnostic and focus where the potential for simplification is greatest. Targeting only certain policy areas – such as the Green Deal – would be misinterpreting companies’ experiences. In Germany’s mechanical engineering sector, for instance, climate and environmental rules account for about a quarter of overall compliance costs – a notable share, but not the main driver of compliance burdens. Labour law, taxation, product norms or data protection rules together tend to weigh more heavily on businesses.

- Second, not every rule requires simplification. Directives or regulations serve defined objectives. When legislation targets companies, compliance costs are expected. If the law is well-designed, proportionate and effective, simplification may not be necessary, even if companies or lobby groups raise concerns about red tape.

The guiding question should be: Which rules create demonstrably high compliance costs while failing to deliver their intended impact – or could achieve the same impact at lower costs? Put differently: where can simplification both ease compliance and strengthen the EU’s competitiveness by making rules clearer and more consistent? Answering this requires more than anecdotal input and should be based on evidence.

3. Design of technically sound proposals based on evidence

Once rules are selected for simplification, the Commission must design proposals that reduce compliance costs while maintaining the policy objective.

Simplification can take many forms. Amending legislation may involve streamlining it with other laws, removing redundancies or clarifying legal language. Sometimes better guidance or delegated acts may be more effective than revising legislation. In other cases, repealing and replacing a law may be a good option too.

The key is evidence. Proposals should be grounded in stakeholder consultations, impact assessments and policy evaluations drawn from the Better Regulation Toolbox:

- Stakeholder consultations help identify challenges with existing rules and can be a good place to test simplification ideas. Broad consultation usually delivers better results.

- Evaluations of the existing law show whether it is achieving its goals, what could be improved, and what the implementation costs are. Robust evaluations allow simplification efforts to target the most pressing needs.

- Impact assessments determine whether proposed changes reduce costs without compromising objectives. They should also define clear criteria for evaluating the success of simplification.

Together, these tools are essential for simplification. They ensure that the proposed approach is not arbitrary but rooted in evidence and delivers on the goal of cutting red tape for companies.

4. Political consensus on goals and scope for successful rapid simplification and legal predictability

Simplification is not a technocratic exercise – it must pass through political processes. For companies, this political dimension matters greatly: The process of changing laws creates legal uncertainty, especially when rules are already in implementation. Firms that have invested in processes, staff, and strategic decisions rightly expect regulatory stability. Sudden legal shifts or prolonged debates in the Council and EP can erode trust in the durability of future EU legislation. Regulatory predictability is itself a competitive asset – without it, Europe becomes a less attractive place to invest.

This is why simplification requires building an early political majority in the Council and EP.

When speed is the goal, this step is not optional – it is the only way to ensure companies see swift burden reduction and avoid prolonged uncertainty. That in turn requires a shared understanding of both the goals and the scope of simplification:

- First, an early alignment on which laws to target and the goals behind it is necessary: Simplification or deregulation – clarity on this is important to avoid political deadlock.

- Second, political agreement on the scope of simplification will ensure a smoother legislative process. For a given law, should reporting data points be reduced or should the number of companies reporting also change? Reaching clarity on this with co-legislators will ensure easier negotiations and help to deliver burden reduction faster.

The Commission can sustain a political majority only by sticking to what was agreed with Council and EP: if simplification is the goal, proposals must reflect that. This is even more important when amending existing laws: Co-legislators will struggle to agree on amendments if they are not aligned and end up renegotiating the purpose of specific rules. Agreeing on goals/scope and transparent communication early in the process allows businesses to plan for compliance and adapt accordingly.

Understandably, reaching consensus on both objective and scope is not easy, given the Council and the EP often take different positions. But without it, the Commission’s rapid Omnibus agenda cannot succeed.

The way forward: An Omnibus agenda that delivers on cutting red tape

The Omnibus agenda is here to stay – and for good reason. With the review of the entire EU rulebook ahead, many more simplification proposals will follow in the years to come.

The success of this agenda depends on the Commission delivering genuine simplification. That means early alignment with co-legislators on goals and scope, and technically sound measures grounded in evidence – not the interests of political groups or business associations.

In practice, this means four things: clarity on goals, evidence to identify the right rules, technically sound design using Better Regulation tools, and early political alignment with Council and Parliament.

The Commission has already learnt from criticism. For example, on some of the forthcoming simplification proposals, it is conducting more transparent stakeholder consultations and “implementation dialogues” to gather evidence on which rules need simplification and why. This is promising step.

If done well, simplification can make Europe’s high standards work more effectively and predictably, strengthening competitiveness. Ultimately however, competitiveness also depends on a broader strategy: fostering innovation, deepening the single market and ensuring regulatory and political stability. Properly designed, simplification can support these goals and help secure Europe’s long-term competitiveness.

About the author

Claudia-Dominique Geiser is Senior Expert for EU economic policy in the Europe Program at the Bertelsmann Stiftung. Her focus is on EU single market policy and Germany’s role within the EU.

Write a comment