Economic security is fast emerging as a strategic priority for Europe as a whole. The EU is expanding its partnerships with like-minded allies, yet its engagement with the UK remains merely nascent. This policy brief shows that, despite taking different approaches since Brexit, the two sides share notable vulnerabilities in goods trade and a common interest in upholding an open, rules-based economic order — providing a solid foundation for renewed cooperation. Progress will require steady, practical steps under the new Strategic Partnership. But long-term success hinges on two prerequisites: UK willingness to re-engage with EU trade governance and closer foreign policy alignment on the strategic challenge posed by China.

Introduction: A strategic partnership without geoeconomic heft

The EU and the UK are entering a new phase in their post-Brexit relationship – one defined by geopolitical convergence but limited geoeconomic coordination. When Keir Starmer, Ursula von der Leyen and Antonio Costa met at Lancaster House in London for their political summit in May 2025, they declared the opening of a “new chapter” in relations. The summit produced a package of measures that turned the cautious talk of a “reset” –the Labour government’s phraseology after the party’s July 2024 election victory – into a “strategic partnership” formally endorsed by both sides. It included a roadmap for negotiations to improve post-Brexit arrangements and a new Security and Defence Partnership (SDP).

While geopolitics lay behind this renewed cooperation, one strategically vital aspect was absent: economic security. The Lancaster House declaration affirmed the importance of “free, sustainable, fair and open trade”, and the SDP commits both sides to “explore ways to exchange views on external aspects of their respective economic security policies”. But this language is studiously vague and devoid of concrete commitments to address shared geoeconomic risks that threaten Europe’s collective security and resilience.

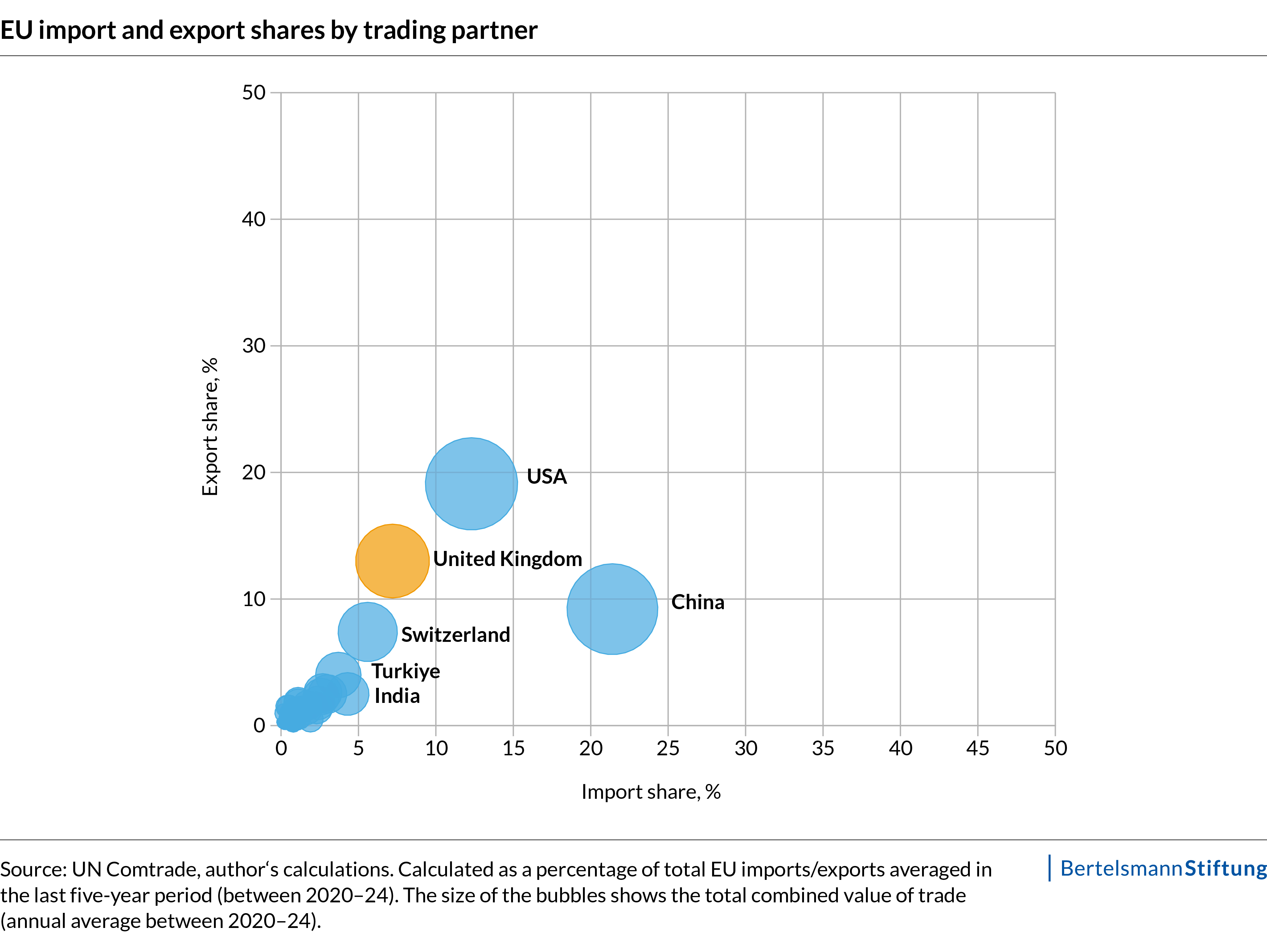

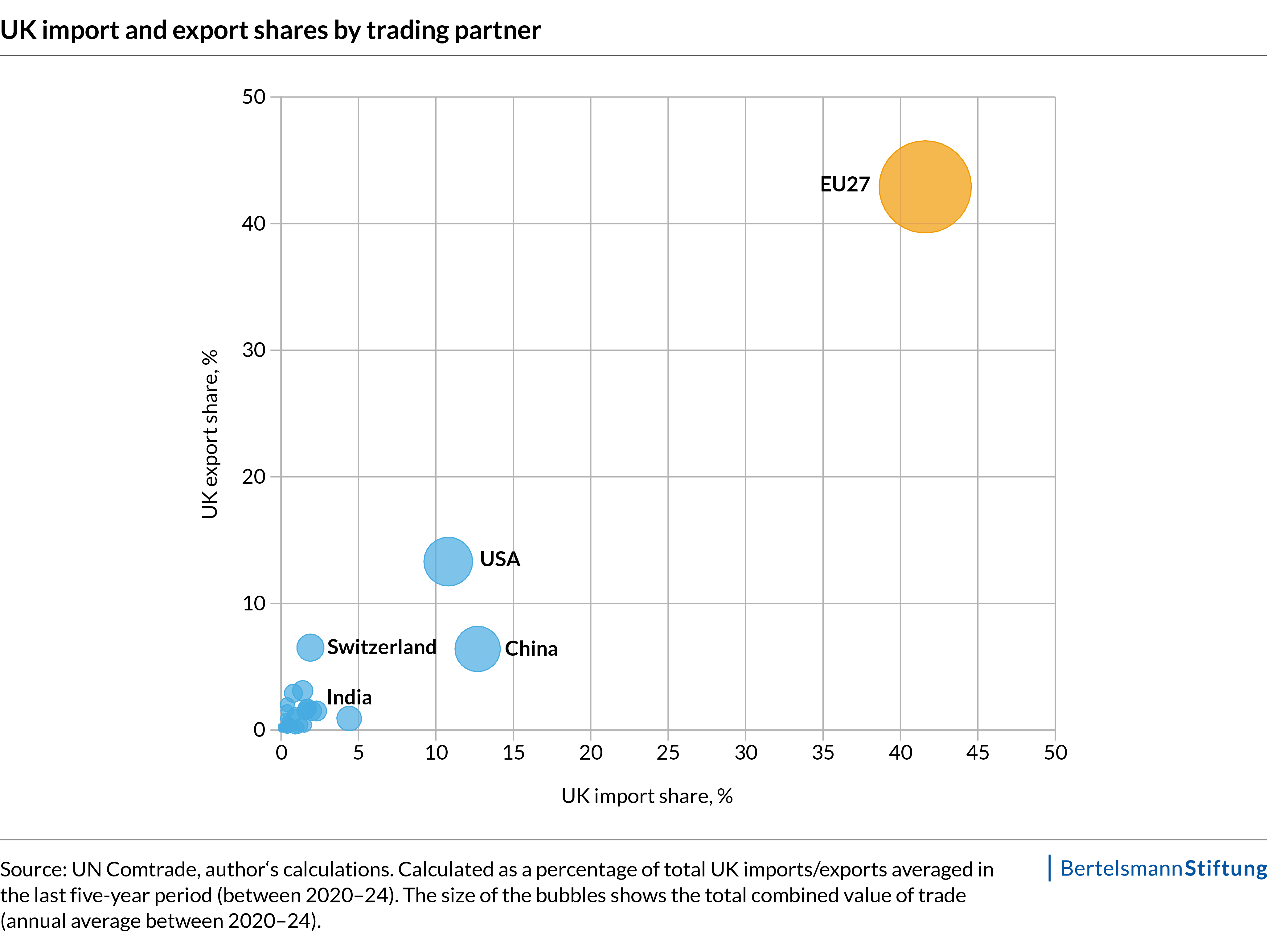

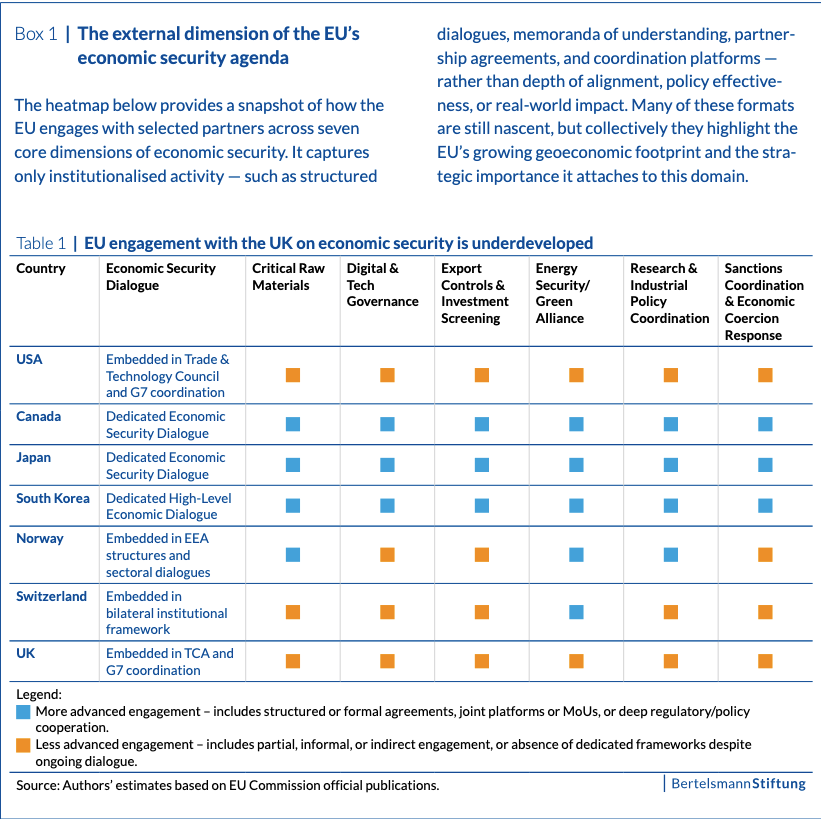

The omission is striking. Both sides increasingly recognise the nexus of economics and security as central to their strategic planning. Their economies also remain deeply intertwined: the EU is the UK’s largest economic partner by far, while the UK is the EU’s third-largest partner – after the US and China, both of which are fraught with major challenges (see the following two charts below). At the same time, the EU has been expanding economic security partnerships with “like-minded” partners worldwide, but the UK is among the few major partners without a structured framework for cooperation (see Box 1).

This gap is more than a mere oversight. It reflects deeper structural and political factors: for the EU, the UK’s decision to leave the EU single market has excluded it from the many collective initiatives on economic security, while in the UK wariness of any arrangements resembling “shadow membership” has persisted – even under the Labour government. Ambition thus remains limited. Nonetheless, the case for economic security cooperation deserves to be reassessed.

This paper’s premise is that any viable framework must start from a recognition of shared interests. To this end, we conduct an empirical mapping of bilateral trade vulnerabilities to provide evidence for cooperation. In a second step, we analyse joint offensive interests with a view to retaining an open and reliable geoeconomic order. Building on this, we set out proposals designed to help both sides capitalise on overlapping exposures, strategic interests, and institutional capacities. These suggestions also embrace political realities and structural barriers that have so far constrained cooperation, the specific risks and benefits for each side, and the formats most likely to enable practical joint action without undermining the EU’s internal coherence in how it deals with third partners.

Finally, while this paper focuses primarily on trade-related vulnerabilities as a concrete area where immediate progress can be made, economic security encompasses a broader set of issues, from protecting critical infrastructure and cyber threats, to addressing technological leakage and risks. These are not fully explored here but could undoubtedly prompt further cooperation.

1. Divergent approaches: Comparing EU and UK responses to economic security

The European Commission’s 2023 Economic Security Strategy firmly established the issue on the EU’s strategic agenda, identifying four key risk areas: critical supply chain dependencies, threats to critical and cyber infrastructure, technology leakage, and economic coercion. Alongside a suite of internal measures to bolster resilience, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has framed economic security as a central pillar of a “new economic foreign policy”, linking internal policy instruments with a more outward-facing agenda. Since then, the EU has expanded its legislative toolbox, introducing the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), and proposals for a strengthened investment screening regime together with more coordinated controls on the exports of dual-use technologies. The Commission is now working towards a formalised “economic security doctrine” to align policy instruments across member states within a clearer framework.

These ambitious goals , however, face structural and political limits when it comes to success. First, competences are divided between Brussels and member states in crucial areas such as industrial policy, investment protection, and export controls, limiting the scope for collective action. Second, divergent national interests – from differing attitudes to China to sharp disagreements over trade defence tools – threaten to undermine policy coherence and collective unity. Third, there is a tension with the interests of many European businesses, many of which prioritise openness and global integration and resist any measures they see as protectionist.

The UK, having exited the EU before economic security rose up the geopolitical agenda, has been slower to adapt. Successive governments have preferred a lighter-touch approach, both legislatively and institutionally. The 2021 National Security and Investment Act (NSIA), allows government intervention on national security grounds but relies heavily on ministerial discretion. Most interventions have targeted foreign acquisitions in defence, telecoms and energy, though the regime has also extended to intellectual property and domestic corporate restructuring, gradually broadening from being a foreign-investment screen to a tool for controlling sensitive sectors irrespective of ownership.

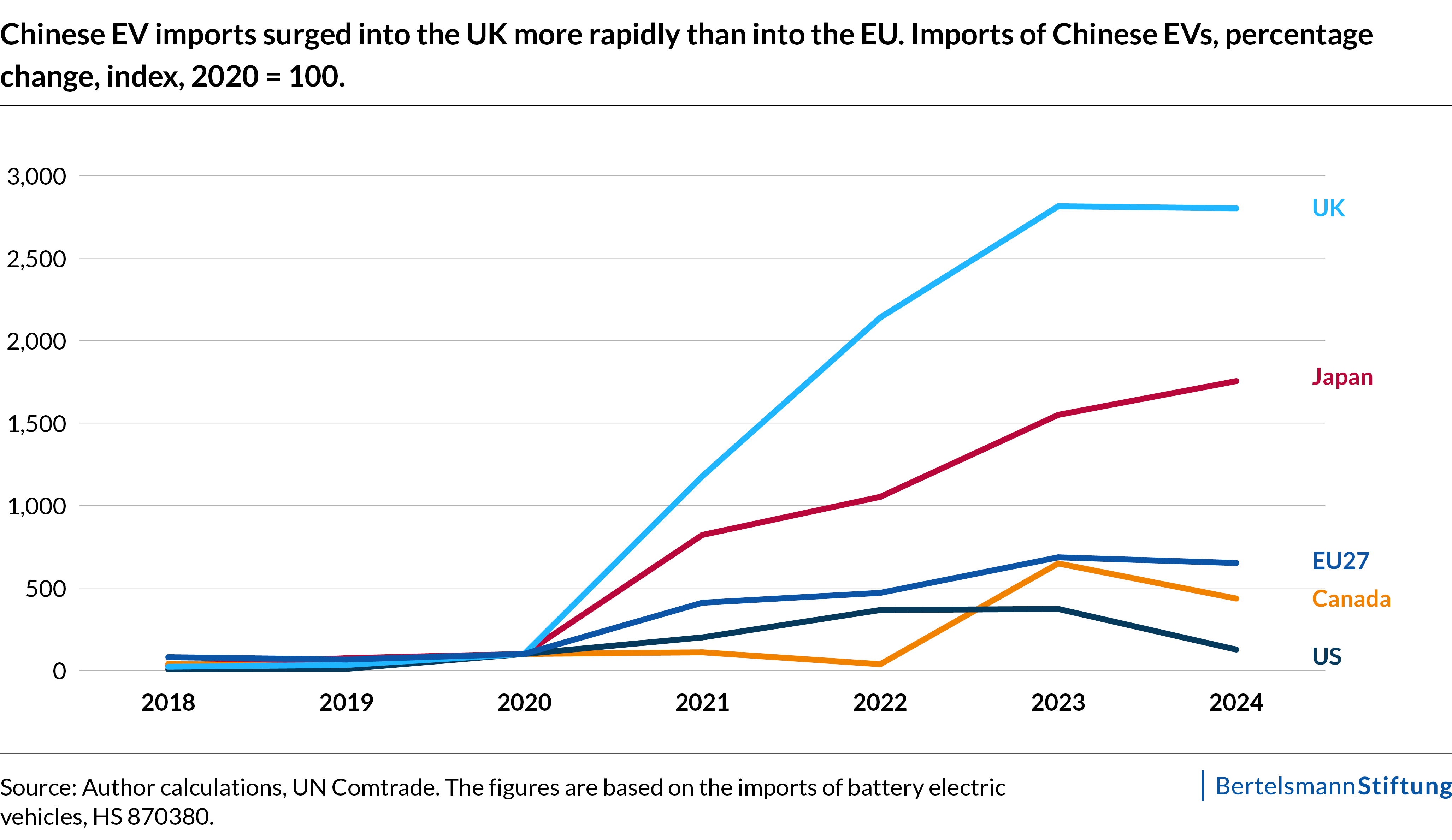

Not only is the UK’s approach less rules-driven than EU frameworks, but the British government has been more cautious about deploying defensive trade tools, suggesting higher risk tolerance than evident in Brussels. The handling of Chinese imports of electric vehicles (EVs) illustrates this. In 2024, the EU imposed ‘countervailing duties’ on these imports – defensive tariffs aimed at offsetting unfair subsidies. The UK declined to follow suit – even though Chinese EV imports have surged into the UK four times faster than into the EU since 2020 (see chart below).

The Labour government has signalled a shift in policy. In its Trade Strategy, released in June 2025, it has pledged to introduce a new trade defence instrument (potentially modelled on the EU’s ACI), reform the post-Brexit trade remedies regime, and establish a dedicated Economic Security Advisory Service to support engagement with business. These measures suggest a firmer stance on London’s part, though the underlying tension with the UK’s traditional free-market instincts – still entrenched in parts of Whitehall – remains.

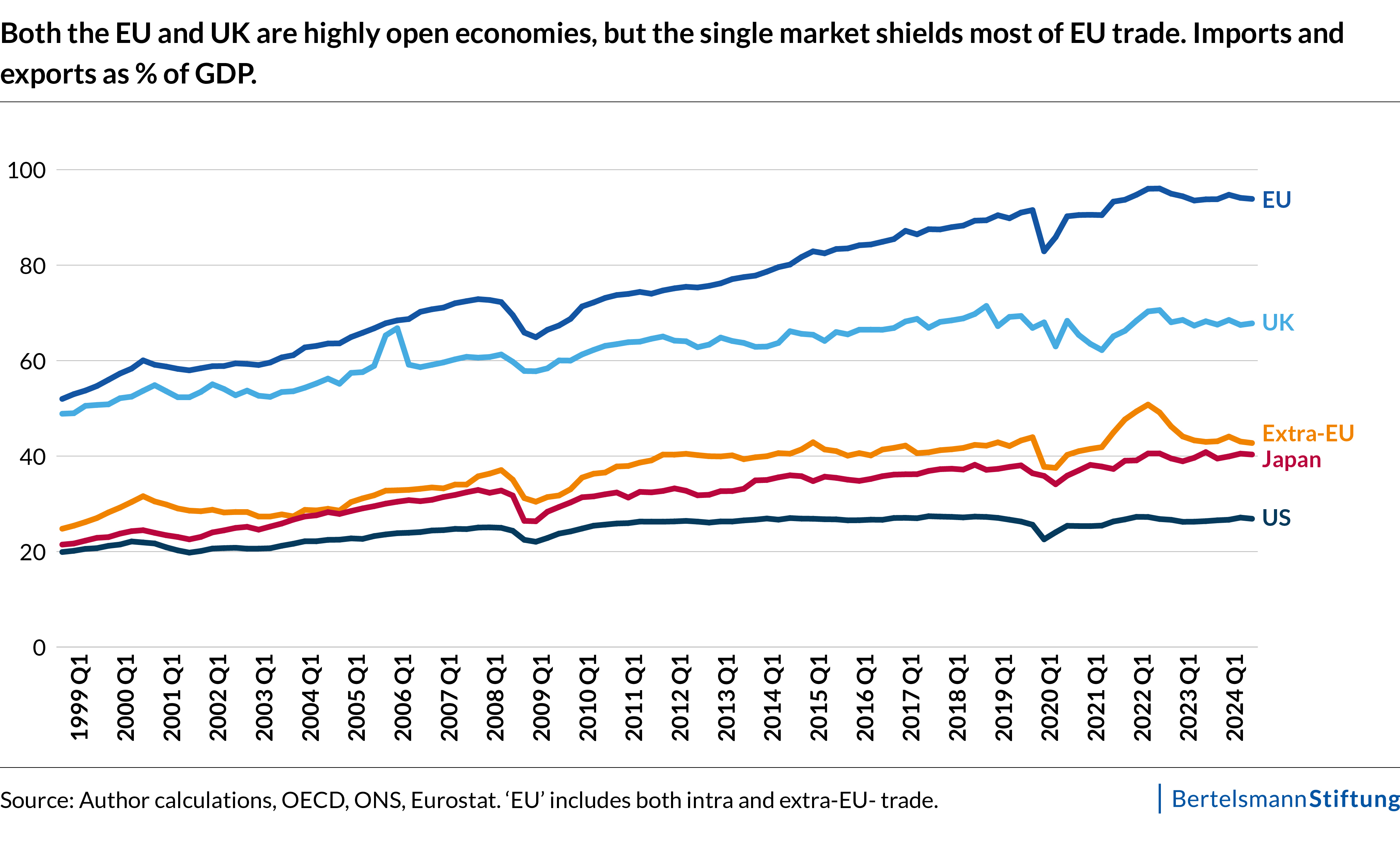

This suggests that the responses of the EU and the UK to many economic security challenges have failed to converge. On the one hand, this reflects different policy preferences: Brussels has favoured formalised, rules-driven instruments, while London has prioritised flexibility and executive discretion and presented “agility” as a relative advantage in responding to new threats. On the other, it also reflects the different geoeconomic baselines to the domestic economic security debates (see chart below). For the UK, trade accounts for nearly two-thirds of its GDP, leaving it simultaneously dependent on trade for economic growth but also highly exposed to external shocks. Moreover, since the pandemic and Brexit, the UK’s trade position has weakened, leaving it little room to restrict openness by curbing imports or foreign investment. The EU, while also highly open, has its external trade-to-GDP ratio closer to that of other advanced economies, benefitting from the scale of the single market that enhances its bargaining power and cushions external shocks.

2. Shared defensive interests

Despite divergent approaches, opportunities for cooperation exist in areas where vulnerabilities overlap and both sides share ‘defensive’ interests, and in domains where they have aligned ‘offensive’ objectives in seeking to gain geoeconomic influence in the global arena.

A first step has been to identify the extent to which the two sides face common vulnerabilities. Using detailed product-level trade data covering over 5800 products between 2021 and 2023, we conducted a systematic mapping of trade dependencies for both the EU and the UK (see technical annex for full details). We identified product-level dependencies where both sides depend on the same dominant third-country supplier, accounting for 50% or more of total imports of that product as well as those areas where supply chains create mutual dependencies.

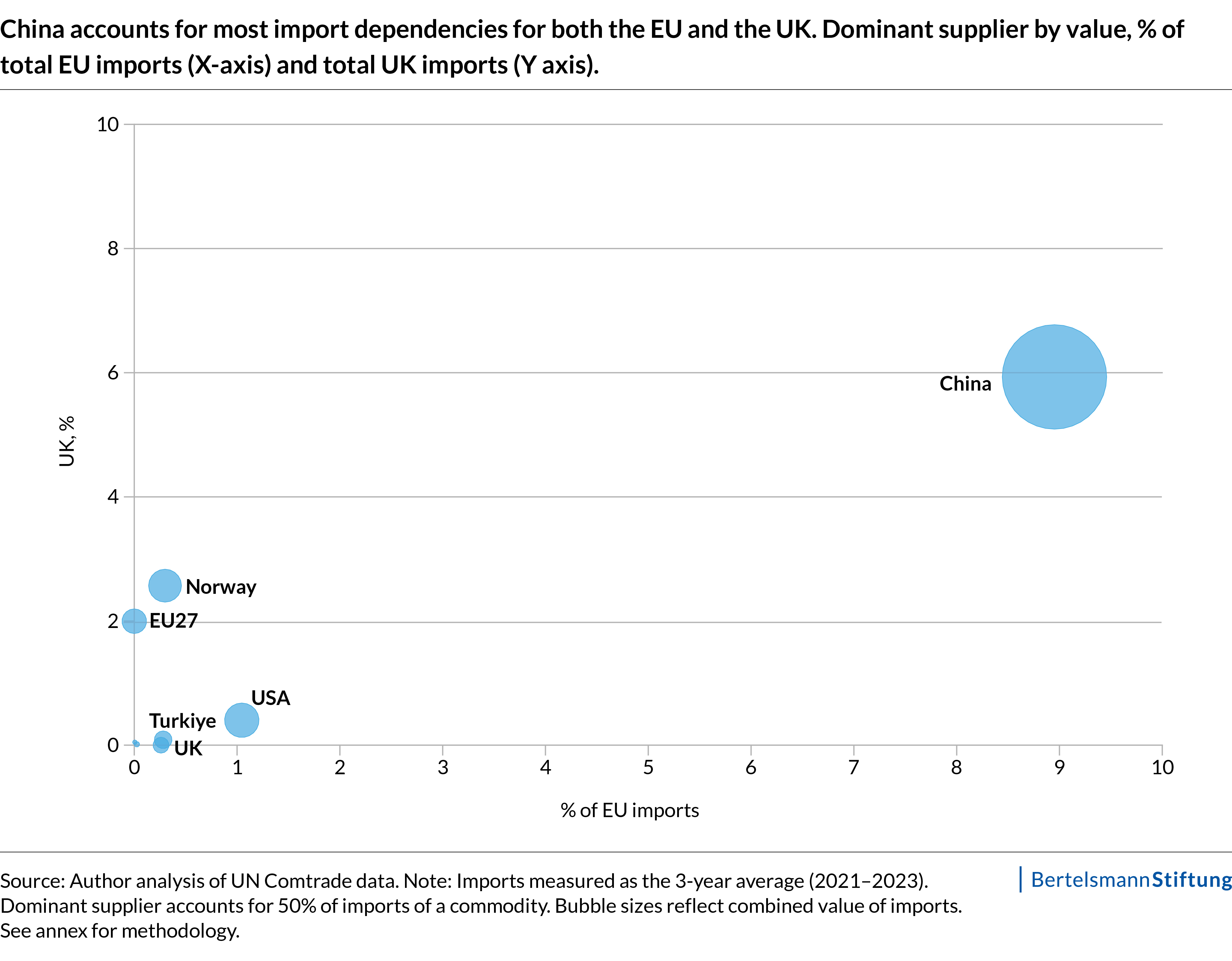

We found that both the EU and UK are highly dependent on dominant suppliers. Nearly 20% of EU imports and 15.4% of UK imports by value are subject to this vulnerability. Most of these dependencies are concentrated in imports from China, as the chart below shows. For the EU, China is the dominant supplier for 554 imported products (8.9% of EU imports); for the UK, China accounts for 438 (5.9% of UK imports). Dependencies on other partners such as the US, Turkey and other Asian countries are negligible in comparison. In effect, for both economies, external import risks are synonymous with their exposure to China, though this exposure is somewhat greater for the EU.

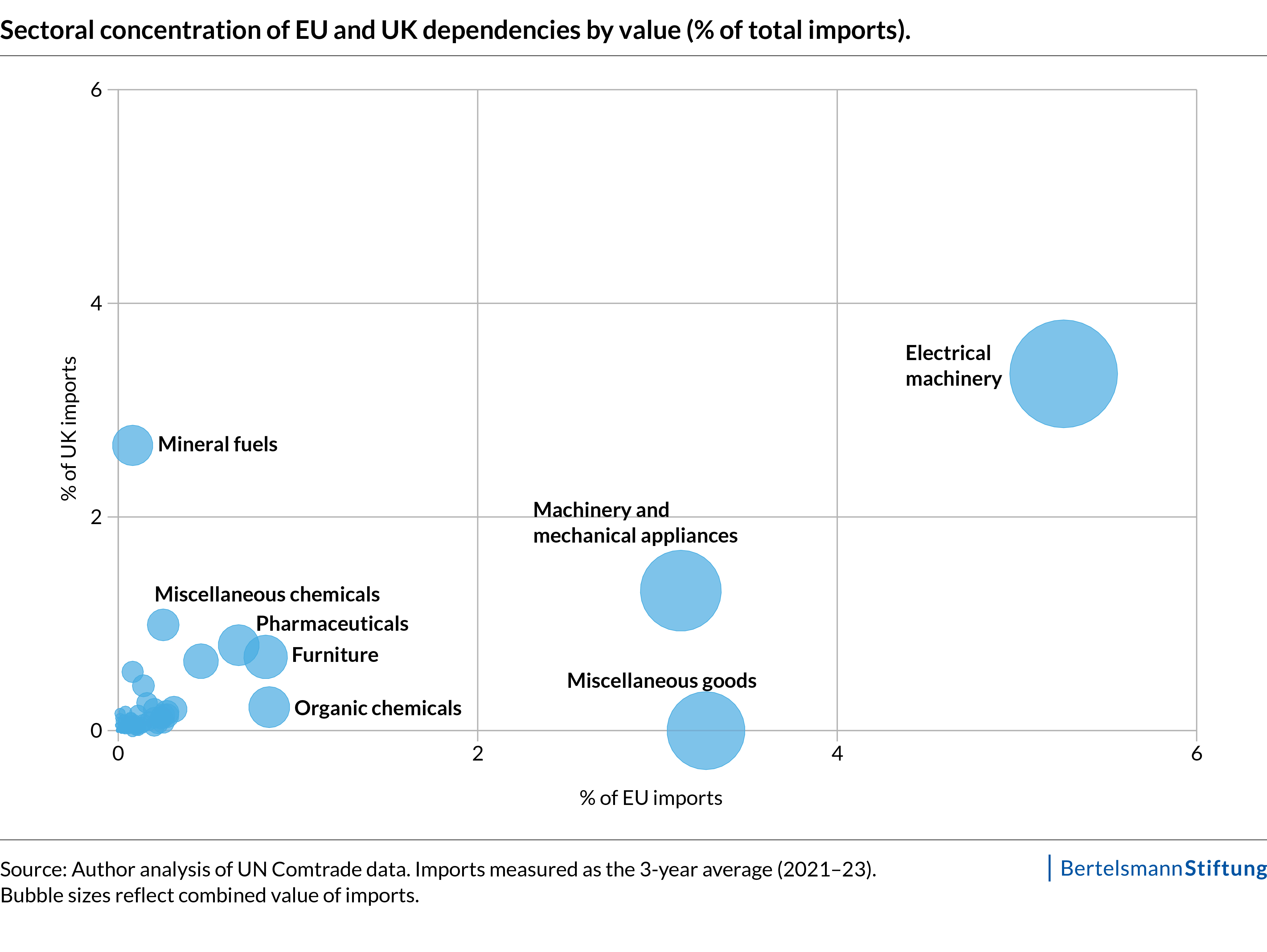

Around 7% of imported products (335 HS-6 products) are dominated by the same third-country supplier, mainly China (219). The shared exposure to China for this subset of products is not negligible: it represents 5.5% of EU imports and 4.1% of UK imports. The heaviest shared exposures to China are in electronics (laptops, smartphones, monitors), solar panels, and rare earths – all segments dominated by China, as demonstrated in the chart below. While some are related to low-risk consumer goods, others include strategically important areas such as high-tech industrial goods and key inputs such as commodities and chemical compounds. It is in those areas – where both sides share the same third-country vulnerability regarding the same product – that material interests in cooperating on diversification of specific product supply chains exist.

Alongside these shared external risks, there are some products where the EU and the UK are dependent on each other. The UK relies on the EU for 438 products (2.9% of imports by value), while the EU is dependent on the UK for just 68 products (only 0.3% of imports by value). UK dependencies on the EU are wide-ranging and include pharmaceutical products, agri-food, industrial goods, automotive components, and chemicals. By contrast, EU dependencies on the UK are fewer but concentrated in some significant niches, such as pharmaceutical inputs, various chemical compounds (e.g. anillin, silver compounds), and seafood. Between two close partners, these mutual dependencies can be a source of resilience, rather than a risk, if they are managed carefully and where ‘partnership tools’ such as long-term contracts or coordinated standards can lock in reliability.

What is evident from this analysis is, first, that both sides face similar risks from supply-chain overconcentration, especially around China, that warrant joint diversification and risk reduction efforts. Second, there are areas where EU-UK supply chains are intertwined, creating mutual interests in safeguarding resilience.

3. Shared offensive interests

Much of the debate on economic security typically focuses on defensive measures – reducing dependencies, screening investments, or responding to coercion. These ‘defensive’ tools are essential for limiting vulnerabilities, but they do not, on their own, enhance competitiveness or shape the rules governing global markets. For both the EU and the UK, the ‘offensive’ dimension of economic statecraft is equally important: projecting influence by setting international standards, mobilising investment into strategic sectors, and building international coalitions that advance European interests.

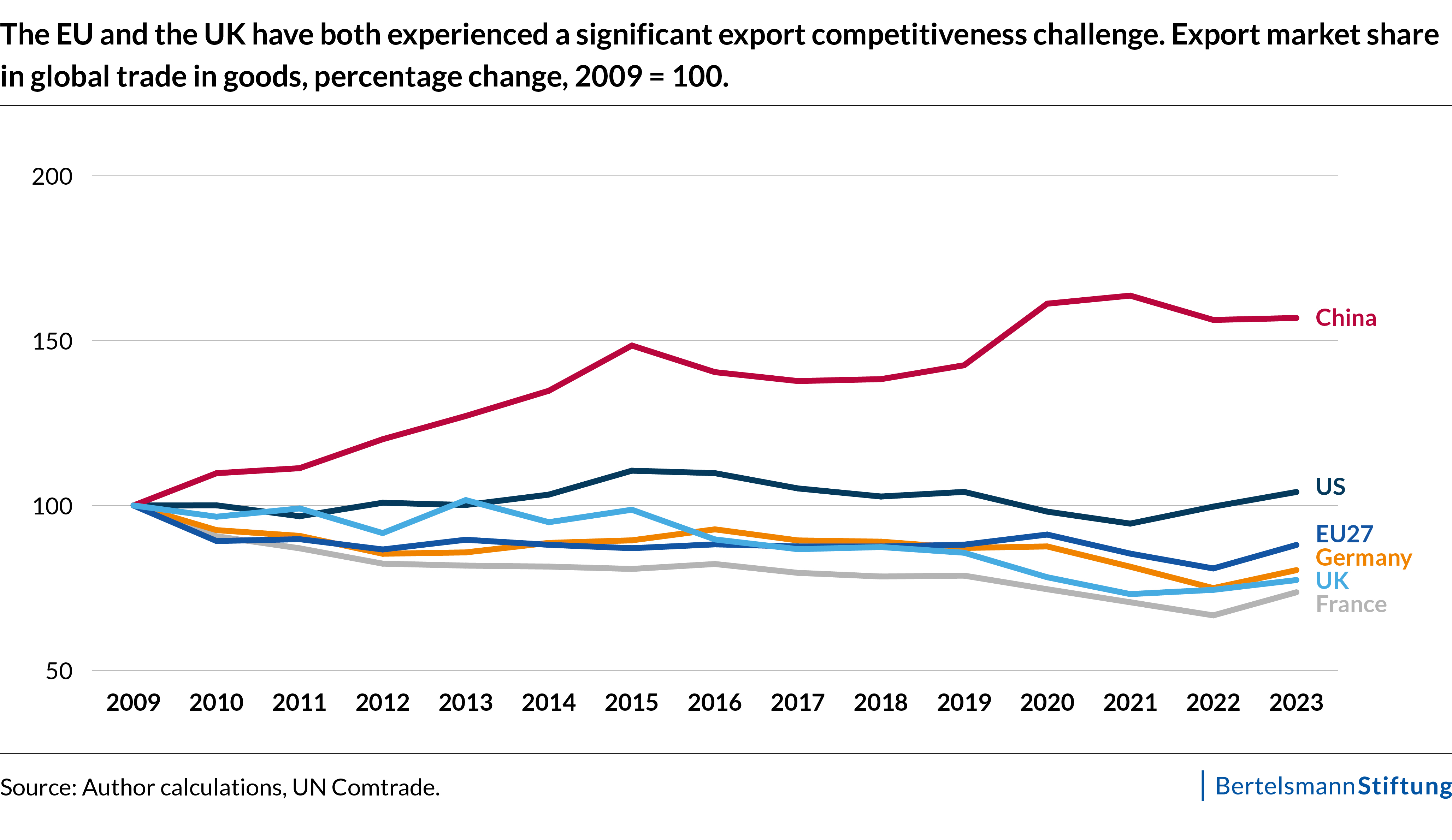

The two sides share a broadly similar assessment of the global economic environment for forging this agenda: both lag behind the US and China in critical technologies such as semiconductors, AI and clean energy; both face persistent challenges to export competitiveness, with their global export shares declining steadily (see chart below); and both depend on the rules-based trading system and are committed to reviving a multilateral global order, through reforms to institutions like the WTO – and/or possible new groupings such as an EU-CPTPP that has been floated.

Three areas stand out where EU-UK ‘offensive’ interests are aligned. First, standard-setting in critical and emerging technologies. Both sides recognise that technological leadership is increasingly exercised not just through innovation capacity but through regulatory power and the ability to embed standards globally. The EU has positioned itself as a regulatory first-mover, with the AI Act, the Digital Services Act, and initiatives in cyber-security and data governance. The UK has pursued a more flexible approach, building credibility through convening power in AI safety and sector-specific regulation. Jointly, they could reinforce one another: aligning approaches to AI risk management, semiconductor resilience, and digital infrastructure would strengthen Europe’s collective ability to export norms, particularly when channeled through international fora such as the G7, the OECD, or standard-setting bodies.

Second, shaping global markets in clean technology and advanced manufacturing. Both sides are exposed to subsidised overcapacity in strategic sectors, most visibly in electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels. The EU’s countervailing duties on Chinese EVs mark a defensive response; the UK’s reluctance to follow highlights policy divergence. Yet both economies ultimately face the same challenge: how to build domestic capacity while avoiding uncoordinated subsidy races. Coordinated investment frameworks, interoperable carbon-border adjustment mechanisms (with the EU’s CBAM launching in 2026 and the UK’s in 2027), and joint procurement standards for clean-tech supply chains could shape demand conditions in ways that attract investment and create scale across the European market.

Third, coalition-building in trade and supply-chain governance. With multilateralism under strain, the ability to organise plurilateral clubs is becoming an offensive tool in its own right. The EU has advanced new partnerships with Canada and Japan and launched the Global Gateway investment platform. The UK, through its accession to the CPTPP and bilateral digital agreements, has gained a foothold in Indo-Pacific trade governance, which can help the Commission’s ambition to increase cooperation with the CPTPP countries. Combining these assets through closer coordination – whether in the G7’s economic security platforms, new plurilateral trade initiatives, or joint infrastructure finance – would amplify the reach of EU and UK rules and increase the pair’s collective bargaining power in global markets.

4. How to cooperate? Towards a Model of Gradual Economic Security Cooperation

The challenge, as in other parts of the EU–UK relationship, is not just to identify shared priorities but to create the right conditions to act on them. While overlapping interests are clear – defensively in reducing risks and offensively in shaping markets and rules – the legacy of political mistrust, institutional asymmetry and diverging preferences continues to weigh heavily. Yet the case for economic security cooperation is increasingly hard to ignore. Without coordination, exploitable gaps will persist, vulnerabilities will deepen, and both sides will find themselves less able to influence the emerging rules of economic statecraft.

Effective cooperation cannot begin with an all-encompassing agenda or full alignment. The task is to move from hesitation to practical steps that are readily feasible but flexible enough to evolve over time. We propose a three-stage pathway: starting with more regular dialogue and information exchange, advancing into functional cooperation, and only then exploring more structured forms of alignment.

- More regular and structured dialogue

The first step should be to establish more regular discussions of respective economic security policies. Such exchanges would allow both sides to assess shared risks, compare regulatory developments, and coordinate responses to global issues. Some of these discussions already take place within specialised committees of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), but there is no dedicated forum. The two sides should consider the merits of a dedicated Economic Security and Resilience Dialogue that could provide a forum at the political level, bringing together the UK Business and Trade Secretary and the EU Trade and Economic Security Commissioner for regular policy exchanges. This dialogue need not be enshrined in a treaty at the outset, but it could gradually be integrated within the TCA framework.

- Deeper cooperation in priority areas

In parallel, both sides can pursue targeted cooperation in those areas where shared vulnerabilities and interests most clearly overlap: energy resilience, supply chain mapping, digital infrastructure security, and screening of inbound investments. The upcoming SPS and energy negotiations between them offer opportunities to pilot such cooperation; electricity market integration, reliability of agri-food supply and joint risk management, involve important aspects of economic security. These initiatives could serve as practical trust-building measures, demonstrating the value of cooperation without requiring formal harmonisation.

- Structured alignment where feasible

Where political will and trust are sufficient, more structured forms of cooperation may follow. These could include coordinated responses to economic coercion, participation in global supply chain platforms, or alignment on critical raw materials standards. Such efforts could draw on existing EU bilateral templates — such as those with Canada or Japan — without requiring the UK to adopt or shadow the EU acquis. The goal would not be full harmonisation, but mutual resilience through alignment on strategic objectives and minimum safeguards. Over time, the dialogue could provide a forum for deciding where such structured alignment is both feasible and politically sustainable, without disrupting EU internal coherence in engaging third partners.

Outlook

The deeper the cooperation, the greater the demands for closer alignment. The EU’s “de‑risking” agenda has become a central organising principle for its economic security policy, while the UK has taken a more cautious approach. For Brussels, closer coordination risks blurring the boundaries of EU competence, particularly if the UK sought influence without accepting elements of the EU’s trade framework. For London, cooperation offers a way to amplify resilience and gain entry point into wider discussions over trade and economic discussions that have so far been difficult to access. But the downside might be a limit to the UK’s independent trade policy, especially in its ability to differentiate itself in talks with other partners and might force it to accept new obligations without reciprocal influence.

More durable cooperation depends on two conditions. First, the UK must be willing to engage with the EU in ways that open the door to alignment with aspects of EU trade policy. Second, both sides must develop a shared strategic understanding on engagement with China, which is plumb centre of the ‘defensive’ agenda. These should not be treated as rigid preconditions but can evolve in line with dialogue and experience.

The immediate priority is not to negotiate a grand framework, but to start with small, concrete steps. Both sides must recognise that they face common vulnerabilities, depend on one another in key sectors, and share an interest in shaping the emerging global order. This should open the way to cooperation that starts with more regular dialogue and practical initiatives in areas of obvious overlap, building trust through tangible results. Over time, as confidence grows, this approach can lead to more structured alignment. That would make economic security a pillar of the EU–UK partnership, anchoring it in today’s global realities and giving both sides a stronger hand in shaping the new geoeconomic order.

About the authors

Jake Benford is Senior Expert Europe and Geopolitics at the Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Anton Spisak is an Associate Fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Write a comment