Against a backdrop of geopolitical tensions, systemic shocks and growing external interference, preparedness has become an imperative for European security. The EU’s Preparedness Union Strategy, issued in March 2025, represents the first comprehensive attempt to turn the shared aim of a resilient Europe into a concrete plan of action. With its broad institutional reach across policy fields, its regulatory powers, and its financial instruments, the EU is uniquely equipped to advance European preparedness beyond military readiness.

However, by scaling a largely national approach to the supranational level without first defining the EU’s specific added value, the Strategy risks turning into a box-ticking exercise with an overly broad agenda that overburdens both Brussels and the member states. To secure political buy-in and enable the EU to contribute credibly to European preparedness, the European Commission should give its agenda substance, focus, and direction by:

• Understanding national contexts to identify common challenges and opportunities for EU action.

• Defining a distinct role alongside NATO to complement efforts and enhance impact.

• Leveraging its strengths to bolster societal preparedness.

European preparedness is essential – but a demanding undertaking

Amid Europe’s new era of insecurity, advancing preparedness has become essential. Russia’s war in Ukraine, mounting grey-zone threats and a series of systemic shocks – from the pandemic to climate-related disasters and large-scale blackouts – have revealed significant vulnerabilities across European societies.

Europe’s deep interdependence makes it only as resilient as its weakest link. Robust national preparedness must therefore come first, but it needs to be complemented by stronger coordination and cooperation across the Union to ensure that national systems work coherently when crises cross borders.

Advancing preparedness in both individual member states and the Union is a complex task. Unlike traditional defence, it encompasses all hazards – from natural disasters and cyberattacks to armed conflict – and requires close coordination between civilian and military actors, as well as the active involvement of public institutions, private stakeholders, civil society and citizens.

At the European level, the complexity increases further. Responsibilities are dispersed across institutions and governance levels, with limited coordination and overlapping agendas. Within this patchwork of preparedness efforts, NATO – drawing on its Cold War legacy and established defence mandate – has defined its role through baseline requirements, shared resilience objectives, and a robust culture of planning and exercising. The 2025 Hague Summit added a new 1.5% spending target for civil preparedness, giving the Alliance greater coherence and strategic direction. By contrast, the EU’s Preparedness Union Strategy comprises 63 disparate actions with no clear unifying focus.

For the EU – already stretched in its pursuit of credibility in defence, struggling with coordination fatigue and facing collective-action dilemmas – implementing preparedness is an uphill task. Preparedness remains primarily a national responsibility, and only eight member states currently advocate a stronger EU role. Political sensitivities, concerns over Commission overreach and the diversity of national systems and administrative cultures all constrain ambitions for a more EU-led approach. The comprehensive nature of the concept itself poses an additional challenge for many governments that lack the necessary traditions or resources for such wide-ranging preparedness.

These constraints risk draining momentum from the EU’s preparedness agenda. To contribute effectively to Europe’s overall preparedness, the Preparedness Union must not become another strategy left to gather dust. The coming year offers a critical window of opportunity: in 2026, both NATO and the EU will advance their respective frameworks, providing a chance to align efforts and demonstrate that preparedness can deliver tangible results.

To chart a way forward, the following analysis examines what the EU preparedness initiative has achieved so far, what remains lacking and how the EU’s competences compare and connect with those of NATO.

The Good: Groundwork laid, mindset shift underway

Strengthening resilience has long been an EU objective, but it only gained practical shape with former Finnish President Sauli Niinistö’s 2024 report on strengthening Europe’s military and civil preparedness. The Niinistö report triggered a shift in mindset, reframing security and defence as a shared responsibility extending beyond defence ministries and armed forces to entire governments and societies. Building on this, the Commission launched the EU Preparedness Union Strategy in March 2025 – the first comprehensive attempt to translate resilience into a concrete agenda and to address cross-sectoral risks more effectively.

As a result, preparedness evolved from a niche concern confined to civil protection or health emergencies to a core pillar of European security, alongside defence and internal security. Its all-hazards, whole-of-government and whole-of-society principles reflect a modern understanding of security that transcends the boundaries between internal and external policy domains – an approach well suited to Europe’s evolving grey-zone reality. The Strategy’s 63 actions demonstrate the EU’s ambition to play a more active role in strengthening civil preparedness in cooperation with partners such as NATO.

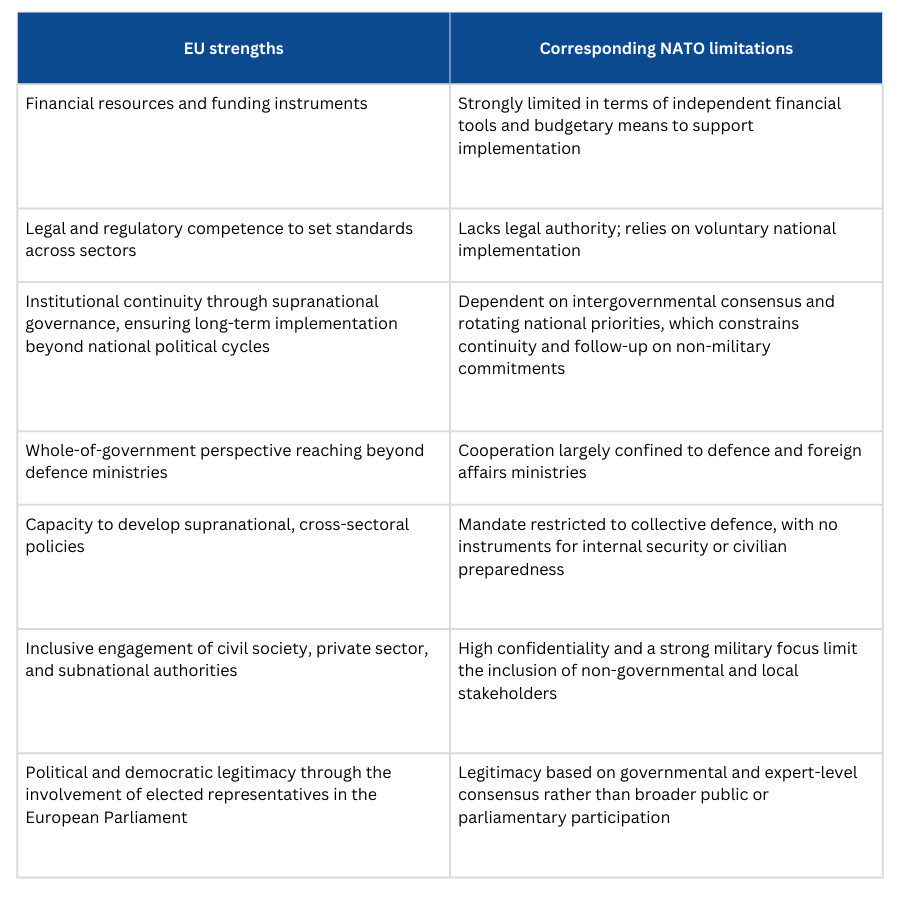

The EU also holds distinct comparative advantages in promoting preparedness (see table 1). Its financial resources, regulatory instruments and supranational reach enable it to translate political intent into tangible, cross-sectoral initiatives – engaging ministries beyond defence as well as regional authorities, civil society and the private sector. This inclusiveness lends the EU both democratic legitimacy and a societal reach that NATO, by design, cannot match.

Table 1: The EU’s comparative advantages in preparedness

The Bad: Overreach, fragmentation and structural limits

Progress to date has also revealed the limits of the EU’s approach. What may appear coherent from the Commission’s perspective often proves overly complex and detached from national realities. This reflects a top-down dynamic that risks losing sight of practical needs. Bringing preparedness to the EU level cannot be a copy-and-paste exercise of the Finnish model. What works in a small, cohesive state with a long-standing preparedness culture cannot easily be scaled to a union of 27 members with differing systems, resources and threat perceptions. In seeking to adapt a national concept to the supranational level, the Preparedness Union has become so broad that it verges on overreach. Rather than providing operational value, it risks overwhelming both Brussels and the member states. As a result, it risks turning into a procedural, Brussels-driven box-ticking exercise rather than a practical framework for implementation.

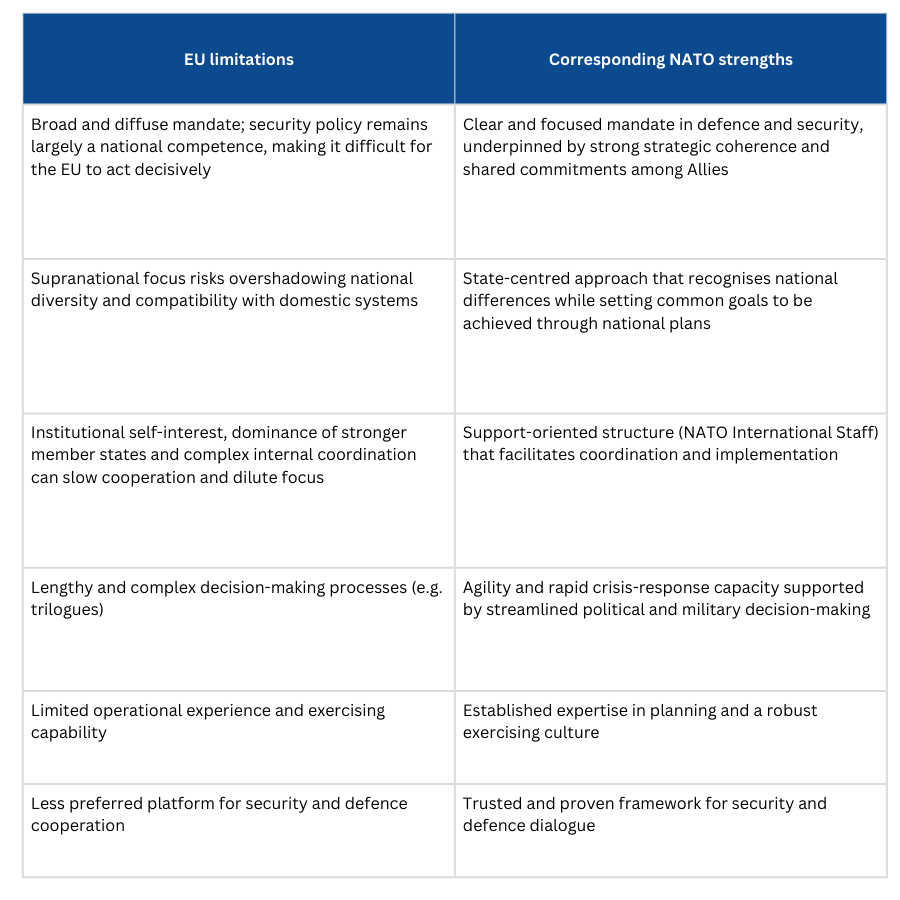

Unlike NATO, the EU operates under significant institutional constraints (see table 2). Its role in security depends on negotiation and consensus-building, and its supranational approach often leaves limited scope for national diversity. This poses particular challenges for preparedness, where national context matters greatly – shaped by societal culture, geography and the interplay between civil and military institutions. Institutional self-interest or the influence of stronger member states can crowd out pragmatic cooperation, while lengthy decision-making processes hinder timely delivery. Whereas NATO benefits from a well-established culture of planning and exercising, the EU frequently lacks the mechanisms to translate strategic intent into operational action.

Table 2: NATO’s comparative advantages in preparedness

The Ugly: EU-NATO coordination without cooperation

The EU’s institutional weaknesses are compounded by Europe’s persistent coordination gap. Although both the EU and NATO aim to strengthen resilience, genuine cooperation between them remains elusive.

To enhance Europe’s ability to withstand crises, military and civil preparedness must advance in tandem – both at national and European levels. Defence and civilian actors need to plan for shared threat scenarios, prepare jointly and coordinate their responses. Achieving this requires the EU and NATO to align their respective preparedness efforts to ensure complementarity. Such alignment would ideally maximise value for member states and strengthen Europe’s overall resilience.

In practice, cooperation remains limited to basic information exchange and ad hoc working-level contacts. The Structured Dialogue on Resilience functions largely as a platform for comparing notes, constrained by political obstacles – above all, the unresolved Cyprus issue – that continue to block deeper collaboration and intelligence sharing. As a result, NATO does not disclose the resilience gaps it identifies, even when the EU holds the tools to address them. The Commission is therefore left to act independently, engaging directly with member states and stakeholders to set priorities and define its niche within Europe’s preparedness landscape.

Taken together, the three dimensions explored in this analysis – the good, the bad and the ugly – illustrate both the promise and the pitfalls of Europe’s preparedness agenda. The EU has built a strong conceptual foundation and possesses distinctive tools for advancing preparedness, but complexity risks stalling progress. Without decisive political and institutional action, the Preparedness Union may lose momentum before it has a chance to mature. Signs of fatigue are already visible: preparedness was omitted from President von der Leyen’s 2025 State of the Union address, while the new Readiness Roadmap 2030, drafted in response to Europe’s evolving grey-zone challenges, focuses exclusively on military readiness .

The way forward: Three steps towards a stronger role for the EU

A pragmatic, needs-driven approach could make the Preparedness Union one of the EU’s most meaningful contributions to European security. If the EU fails to act, the window of opportunity will close quickly.

To make a tangible contribution to Europe’s resilience, the EU must define a clear niche grounded in member states’ realities. This requires answering a few essential questions: What do those responsible for preparedness actually need? How can cooperation among national and local actors be strengthened? Where are NATO’s blind spots? And how can non-NATO EU members be effectively included?

With the next crisis a matter of when, not if, the answers must offer actionable measures. Three priorities stand out:

1. Understand national contexts to build European preparedness

Europe’s preparedness landscape remains fragmented, shaped by differing national histories, threat perceptions, geographies, political systems, civil–military relations, preparedness cultures and approaches to public communication. Even among frontrunners, this diversity is evident: Sweden’s 2024 In Case of Crisis or War brochure, distributed to all households, contrasts sharply with Finland’s more restrained communication style.

Mapping these differences would help identify shared challenges, clarify where the EU adds value, and ensure EU instruments align with national realities.

• Map national models and cultures to identify overlaps and entry points for cooperation. Threat perception, in particular, has become a defining factor: while Russia is viewed as an existential threat in the Nordic and Baltic states, this perception is less pronounced in Western and Southern Europe. Rather than debating which threat matters most, the Commission could facilitate exchanges on shared risks – whether natural, man-made or societal – to foster mutual understanding and build bottom-up solidarity.

• Invest in and coordinate research to build preparedness expertise. Prioritise countries where assessments of national risk landscapes, preparedness capacities, civil–military relations and societal resilience remain underdeveloped. Mapping and synthesising existing national findings would help inform EU policymaking, identify best practices and their transferability, avoid duplication and establish a shared knowledge base for preparedness across the Union.

• Leverage practical experience by facilitating exchange between civil protection actors, private stakeholders, researchers and local authorities. The Finnish–Swedish Hanaholmen Initiative could serve as a model for a broader European forum that promotes a shared understanding and guides EU policy design.

2. Align EU action with NATO milestones to maximise impact

NATO’s strength lies in its clarity, experience and status as the trusted framework for security and defence cooperation. Its well-established culture of planning, exercising and information-sharing provides both credibility and cohesion. The EU can complement this by using its funding instruments, regulatory powers and whole-of-society approach to strengthen resilience in areas beyond NATO’s mandate – and by engaging non-NATO EU members.

With both organisations revising and implementing key initiatives in 2026, there is a valuable opportunity to align new EU actions with existing NATO efforts.

• Build on NATO’s revised baseline requirements. As NATO updates its resilience framework in light of lessons from Ukraine and the EU develops its own minimum preparedness standards, coordination between the two will be essential. The Commission should align its approach with NATO’s to avoid duplicate reporting for member states belonging to both organisations, ensure the inclusion of non-NATO EU members and extend standards to societal functions – such as education, culture and social services – that are essential to morale and civilian resilience. Clearer benchmarks and guidance, modelled on NATO’s system of national plans, would further enhance effectiveness.

• Make the 1.5% spending target work for resilience. As Allies begin applying the 1,5% framework, the key challenge will not be compliance with a loosely defined spending target for non-military but defence-relevant domains, but the effective use of available funds. The EU can add value by supporting European projects that genuinely strengthen resilience rather than enabling creative accounting. Dual-use initiatives – serving both societal needs today and defence readiness tomorrow – would best sustain public support and political momentum.

3. Make strengthening societal resilience a priority

Grey-zone attacks – from sabotage and drone incursions to election interference – have made societal resilience a daily necessity. Europe’s security depends not only on military and technical protection but also on communities capable of absorbing shocks and maintaining essential functions. Beyond legislation on critical infrastructure (the CER directive) and cyberspace (the NIS2 directive), and debates on drone defences or conscription, this broader dimension of societal preparedness remains the missing link in Europe’s security agenda.

While the Preparedness Union Strategy refers to population preparedness, it largely overlooks the role of civil society. Realistically, engaging the “whole of society” must begin with engaging “some of society” – those organisations that serve as multipliers, educators and the backbone of civic contribution. Voluntary firefighters in the Czech Republic, Amateur radio operators in Germany who maintain emergency communication networks, and scouting organisations that promote self-sufficiency and community support – from 72-hour survival kits to basic field skills – all demonstrate how deeply rooted civic groups can build resilience from the ground up. They train citizens, foster social cohesion and can mobilise communities more rapidly and effectively than top-down programmes.

Leveraging its multi-level governance and close connections with civil society, the EU should embed preparedness more firmly in everyday life and local communities.

• Facilitate coordination and bottom-up exchange. The Commission should act as a convener, bringing together national and subnational authorities, civil society actors and practitioners to identify needs, share practices and design approaches suited to each country’s culture and vulnerabilities. Beyond fostering dialogue, the EU can fill a critical coordination gap on the civilian side, where – unlike NATO’s military structures – no mechanism currently exists to map actors and responsibilities across borders.

• Invest in and empower civil society as a preparedness partner. Funding for preparedness and defence in the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) should also support grassroots initiatives and civil society organisations that enhance local resilience. The recently launched European Democracy Shield together with the EU Strategy for Civil Society are steps in the right direction but miss the opportunity to connect more closely with preparedness efforts. Recognising the strategic role of civil society in defence and preparedness must go hand in hand with reinforcing the structures that already connect community life with crisis response.

About the authors

Helena Quis works in the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Europe Programme as an expert on European security and resilience, focusing on comprehensive defence and civil preparedness.

Goran Buldioski is a Senior Fellow at the Hertie School, University of Governance in Berlin.

Kommentar schreiben