The European Commission aims to streamline and simplify its innovation funding by consolidating most of it into a single instrument: the European Competitiveness Fund (ECF). The rationale is clear. The EU’s current patchwork of directly managed funds is marked by a tangled mess of overlapping priorities and fragmented governance. However, simplification for its own sake risks producing a cumbersome superfund that would collapse under its own weight. To make the ECF deliver, its design should follow four guiding principles. First, define a focused scope: only programs that promote innovation, productivity and competitiveness would be included. Second, organize the fund around thematic pillars, each covering the full innovation ecosystem. Third, make full use of the available policy toolbox of funding modes, matching each mode to specific challenges. Fourth, ensure the flexibility to adapt tools as priorities evolve.

1. Introduction

In July, the European Commission will present its proposal for the EU’s next multiannual financial framework (MFF). A key component of the proposal is the consolidation of most budget instruments under the Commission’s direct management into a single vehicle: the European Competitiveness Fund. The current EU funding system – based on excellence – is fragmented and overly complex, burdened by overlapping priorities and inconsistent governance. These structural inefficiencies hinder innovators and industries from accessing support quickly and effectively. The Commission argues that this fragmentation is holding back growth and undermining the EU’s ability to mobilize investment at scale, especially when compared with major global competitors such as the United States and China. With the next MFF unlikely to see a significant increase in size, the Commission is right to argue that the EU can no longer afford such inefficiencies. But the motivation behind the ECF is not purely driven by efficiency considerations: It also gives the Commission greater control and flexibility over how funds are allocated and spent.

The overarching idea is to bring together fragmented funding sources into a single, coherent program that serves as a one-stop shop for EU support aimed at boosting innovation, productivity, and competitiveness. The aim is to simplify processes for recipients, enhance policy coherence, and eliminate redundancy. This aligns with the Draghi Report, which criticized “a lack of coordination among financing instruments” and called for far-reaching simplification (Draghi, 2024). The European Court of Auditors has repeatedly flagged deep-rooted fragmentation, a concern echoed by researchers (Schout, 2024; Laffan & De Feo, 2020). The 2024 Heitor Report – produced by a high-level expert group to inform the next Framework Programme – also strongly advocates radical simplification of the EU’s research and innovation ecosystem (Heitor et al., 2024).

This paper outlines how an effective ECF could be built – and what pitfalls to avoid. The Commission is right to call for structural simplification. But simplification is not an end in itself; it only makes sense if it leads to tangible improvements. A one-size-fits-all consolidation risks doing more harm than good. Rolling all directly managed programs into a mega-fund could dilute accountability, sideline sectoral expertise, and undermine the flexibility needed to adapt funding tools to specific challenges.

To avoid these risks, this paper proposes four key design principles for the ECF:

- Clear thematic scope: Only programs that directly support competitiveness, innovation, and industrial development would be included. Programs with different policy objectives – such as LIFE or the Union Civil Protection Mechanism – would remain outside the ECF. The successor to Horizon Europe would also remain a standalone program, focused solely on frontier, curiosity-driven research.

- Thematic pillars integrating the full innovation ecosystem: The ECF would be structured around pillars such as decarbonization, digitalization, biotechnology, and defense/dual-use technologies. Within each pillar, funding would span the entire innovation lifecycle – from early-stage research to commercialization and scale-up – to ensure continuity and maximize impact.

- Deploy the best funding instrument for each case: The ECF would make use of the full range of funding instruments – grants, equity, guarantees, loans, and blended finance. Each would be applied where it delivers the greatest return per euro spent.

- Flexible and clear governance: The legislation would define only the thematic pillars and allocate funds accordingly. Within each pillar, the Commission would have broad flexibility to reallocate resources. Reallocations across pillars would be made via delegated acts. Specific funding instruments would be proposed by the Commission as part of the annual budget precedure and approved by the legislators. Spending decisions would be made by the Commission, with one directorate-general responsible for ensuring coherence across the ECF, while individual instruments would be managed by the DGs with the relevant expertise.

2. Why consolidation makes sense – up to a point

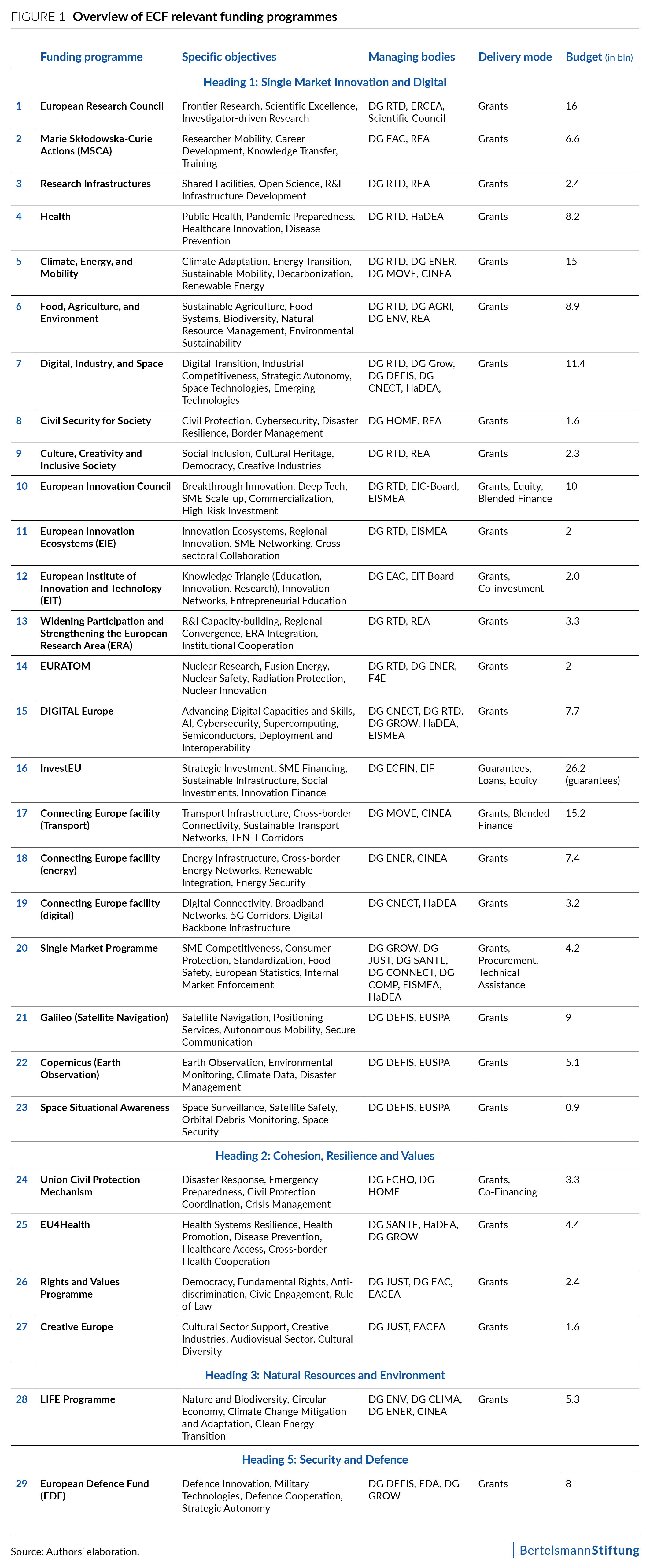

The landscape of funding programs directly managed by the European Commission has grown increasingly complex and fragmented. The 29 largest programs and subprograms under direct management are the most relevant candidates for inclusion in the ECF. These programs operate under varying administrative models, policy goals, and delivery mechanisms – a funding architecture that has developed incrementally into a sprawling patchwork of overlapping priorities rather than a coherent strategic framework. This is more than a bureaucratic headache – it undermines impact. While overlap can, in theory, foster innovation and experimentation, the current EU funding structure lacks the coordination mechanisms needed to turn potential synergies into actual outcomes.

Calls for a strategic overhaul are therefore justified. Right now, the EU is not only trying to do too much with too little, but also attempting to do the same things in too many places – without sufficient coordination to make those efforts add up. In this context, the ECF’s central idea – streamlining, simplification, and strategic realignment – is broadly sound, as a mapping of the relevant funds makes clear.

What would be consolidated? The scope of ECF-relevant programs

The simplest version of the ECF – currently under consideration by the Commission – would create a single pillar within the next MFF that brings together most directly managed funds. This would not include:

- Shared-management funds, such as the structural funds or the Common Agricultural Policy, which are pre-allocated to and administered by member states.

- External action instruments, which cater to political objectives that fall outside of the scope of internal funding instruments

Direct-management funds are centrally administered by the European Commission or its agencies and awarded through competitive, performance-based processes. They are generally geared toward innovation and strategic investment.

The total volume of directly managed funds relevant to ECF consolidation amounts to €169.4 billion in the current MFF period. The lion’s share – around €144 billion – comes from Heading 1: Single Market, Innovation, and Digital. This includes flagship programs such as Horizon Europe (research and innovation), DIGITAL Europe (digital transition), and the Connecting Europe Facility (infrastructure and connectivity).

Most of these programs are integral to the EU’s broader research and innovation agenda. In addition, several other directly managed funds outside Heading 1 could potentially fall under the ECF umbrella, as they are also centrally administered. However, many of these pursue policy objectives not directly tied to growth or competitiveness – such as public health, civil protection, or environmental conservation. One notable exception is the European Defence Fund, which has a budget of €8 billion and figures to become part of the ECF. Its inclusion would reflect the EU’s growing strategic focus on the nexus between defense and competitiveness (European Commission & High Representative, 2024)

2.1. Thematic overlap

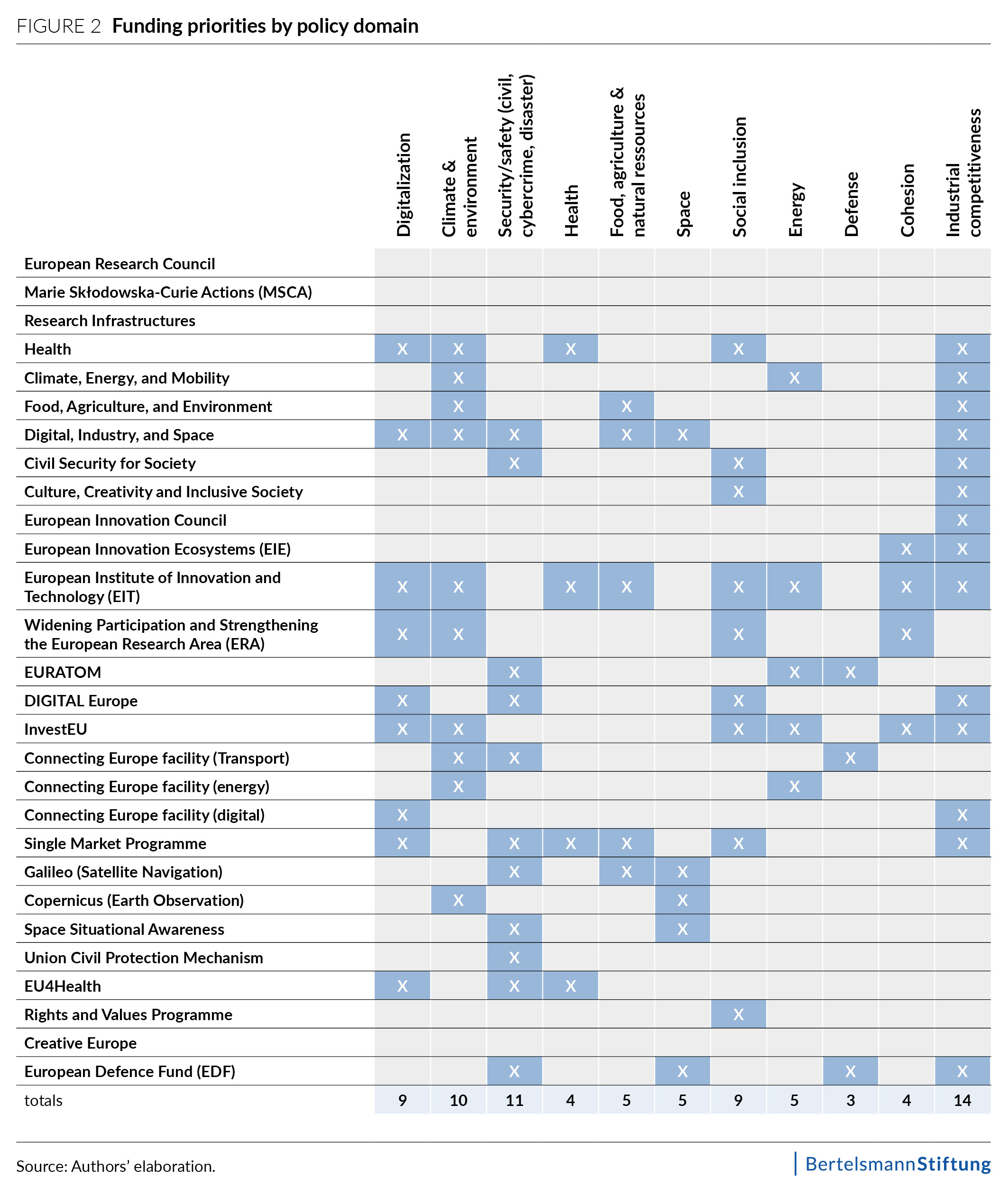

Clustering directly managed programs by their stated objectives and priorities reveals a fundamental lack of strategic direction: Funding priorities are scattered across a variety of programs with no clear thematic focus or consistent set of instruments. This fragmentation undermines synergies and leads to duplication.

As illustrated in Figure 2, many of these programs target similar policy areas and objectives, highlighting substantial thematic overlap. For instance, nine programs explicitly focus on digital priorities, 10 on climate and environmental goals, and 14 on industrial competitiveness.

Are overlaps inherently problematic? Not necessarily. In some cases, intentional overlap is a strategic choice designed to foster synergies and positive spillovers – particularly in complex areas such as research and innovation. Overlapping program objectives can encourage cross-fertilization, specialization, and flexibility. Cross-fertilization occurs when programs deploy complementary tools – such as research grants, infrastructure investment, and skills development – to jointly advance broad goals like digital innovation. Specialization allows different programs to focus on distinct phases of a policy value chain, for example by separating early-stage R&D from market-ready deployment. Moreover, multiple instruments targeting similar objectives can provide space for policy experimentation, support diverse beneficiary groups, and allow quick adaptation to evolving policy needs. In theory, such overlap can help the EU advance broader policy goals and make more efficient use of limited resources. Indeed, most EU programs formally encourage synergies across funding streams.

But in practice, fragmentation often outweighs synergies. Programs cover overlapping thematic areas without clear links to harness synergies. The result is diffuse objectives, thinly spread across numerous instruments with little coordination – leading to competition between programs, redundant efforts, and confusion for applicants, as recent evaluations have shown (European Commission, 2023). While synergies can theoretically boost impact through flexible (alternative) funding, increased scale (cumulative funding), and smoother transitions from research to deployment (upstream/downstream synergies), these mechanisms remain largely underutilized. Instead, the reality more often resembles “double funding” than effective coordination (ECA, 2024a).

Past evaluations have pointed to fragmentation and inconsistent rules across funding streams as major barriers to realizing synergies (Calatozzolo, 2021). An expert review of Horizon Europe reached similar conclusions, calling for greater alignment and coherence across instruments, fewer duplicative programs, and stronger coordination and integration in the successor to Horizon Europe (Heitor et. al, 2024).

This strong overlap across policy domains and objectives underscores the case for smarter consolidation – through clearer thematic distinctions, stronger coordination, and the merger of programs pursuing similar aims.

2.2. Gaps and Incoherence across the innovation ecosystem

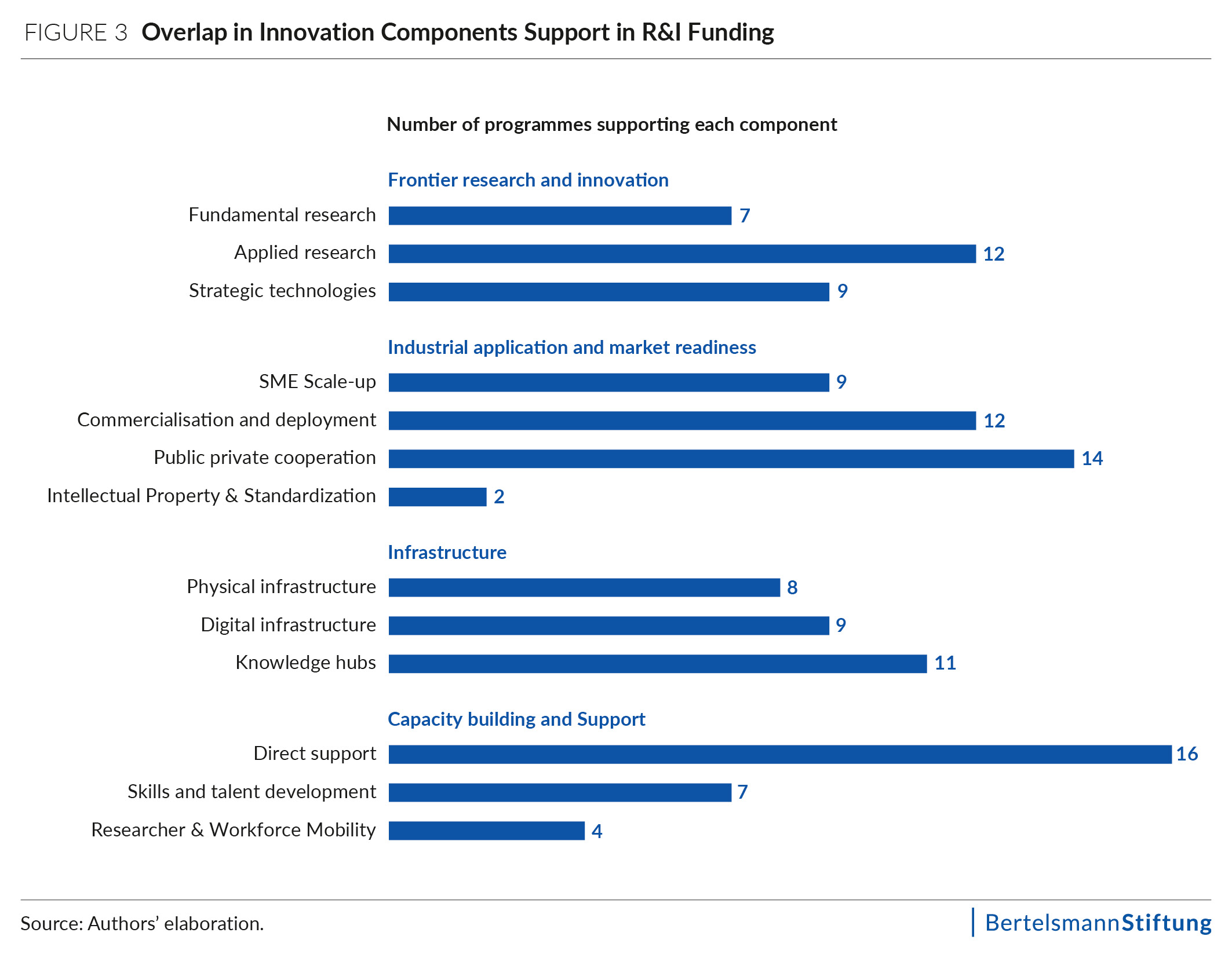

Similar inconsistencies emerge when examining how EU programs support various components of the innovation ecosystem. These include the different stages of the innovation cycle – from early development to scale-up and commercialization – as well as broader enablers, such as direct funding schemes or infrastructure investment. Together, these components form the backbone of a well-functioning European innovation ecosystem.

As shown in Figure 3, overlap in how programmes target these innovation components is just as prevalent as thematic overlap. Many of the identified programs follow similar intervention logics and fund the same innovation components.

Figure 3: Overlap in innovation component support in R&I funding

In theory, if different programs supported complementary stages of the innovation cycle, this could create cumulative impact – enabling funding to flow logically across the entire innovation ecosystem. For instance, Horizon Europe might focus on early-stage scientific discovery, DIGITAL Europe on applied industrial deployment, and the Connecting Europe Facility on infrastructure. This type of coordinated stage-sensitive approach would allow funding to flow logically and seamlessly from research to market.

However, in practice, functional complementarity is rarely achieved. Many thematically aligned programs also fund the same components of the innovation ecosystem without clear boundaries, leading to duplication rather than synergy. Opportunities to reinforce support across stages are often missed As a result, support is often duplicated in some areas, while critical segments – such as commercialization and scale-up – remain under-resourced. This is especially concerning given that breakthrough technologies and industrial applications depend heavily on these later stages. Recent assessments note that only around 5% of Horizon Europe’s budget supports disruptive, high-risk innovation capable of creating entirely new markets (Fuest et al., 2024)

Concrete examples illustrate the challenge. The European Innovation Council, the European Institute of Innovation and Technology, and the European Innovation Ecosystems program all aim to strengthen EU innovation capacity. Yet they overlap significantly in terms of the innovation stages they target, the tools they use, and the groups they serve. Without clearer coordination, these efforts risk redundancy instead of reinforcement. A similar issue arises in digitalization, where programs like DIGITAL Europe, Horizon’s “Digital, Industry and Space” cluster, and elements of the Single Market Programme operate in parallel, with little evidence of integrated development trajectories or complementary design (Public Policy and Management Institute et al., 2024). The problem is also evident in specific strategic technology areas, such as the EU’s AI funding landscape. The ECA found that support for AI was spread across several different instruments and agencies, making it harder to coordinate efforts and limiting the overall effectiveness of EU action in this field (ECA, 2024b).

This disconnect between different stages of the innovation cycle reflects a deeper strategic misalignment in EU R&I policy. The EU continues to excel in frontier science but struggles to translate R&D strengths into industrial competitiveness and technological leadership. Other global players, notably the United States and China, are advancing more effectively in converting research into patents and market-ready technologies, especially in emerging tech sectors (Eulaerts et al, 2025).

These findings point to a clear opportunity for the ECF: to bring greater coherence to the EU’s fragmented funding logic by building a stage-aware, functionally integrated innovation framework. Consolidating related support mechanisms under a unified framework – and assigning clear responsibility for each – would reduce redundancy, enable smoother progression through the innovation cycle, and help develop robust innovation ecosystems in priority sectors.

2.3. Administrative complexity: the issue of governance

The structural inefficiencies described above are exacerbated by administrative complexity. Programs with similar – or even identical – objectives are often managed by different Commission directorates-general or executive agencies, each with its own procedures and interpretations of policy goals. In some cases, a single ECF-relevant program may involve up to seven separate managing bodies. This not only creates duplication and internal competition, but also generates significant bureaucratic overhead.

Subsequently, beneficiaries face a confusing landscape with many different interlocutors, inconsistent eligibility criteria, application processes, and evaluation standards. This fragmentation makes EU funding difficult to access and even harder to navigate. The same fragmentation hampers performance evaluation. Each program relies on its own key performance indicators, reporting timelines, and assessment logic, making it nearly impossible to track collective impact or enforce accountability through conditionality.

2.4. Financial tools without strategy

Although the EU has a wide range of funding tools – ranging from grants to guarantees, equity and loans – grants remain the default mechanism, regardless of policy objective, project maturity, or financial viability. This not only limits the effectiveness of public spending but also weakens the EU’s ability to drive innovation and industrial transformation at scale. Used correctly, a better mix of financial instruments can boost both the efficiency and the impact of public funding. But to date, funding modes are rarely matched systematically with policy objectives.

The notable exception is InvestEU, which brought together over a dozen previously fragmented financial instruments under a single governance structure. By consolidating guarantees and loans within a central platform and deploying them via financial intermediaries in a market-driven manner, InvestEU has demonstrated how financial instruments can be used more efficiently and flexibly across policy domains. Yet this kind of rationalization has not been extended to the broader funding Landscape – particularly to the many grant-based programs that remain fragmented in both scope and governance.

3. Strategic consolidation: toward a smarter, not simpler ECF

The case for consolidation is strong – but a one-size-fits-all “superfund” would likely collapse under its own weight. Merging all centrally managed programs into the ECF risks blurring institutional responsibilities, overwhelming administrative systems, and diluting strategic focus. Not all funds serve the same purpose. Programs like EU4Health or the Civil Protection Mechanism address specific societal needs and need to remain separate to be effective. Oversimplification could create more uncertainty, not less. Overcentralization also invites political interference in areas that require autonomy – especially in basic research, where excellence depends on curiosity-driven, independent science.

At the same time, consolidation needs to account for a delicate trade-off: Too broad a scope risks overloading the fund with too many objectives. Too narrow a scope, on the other hand, risks neglecting areas that still play a critical role in strengthening European competitiveness. A narrowly defined ECF could fail to support these broader goals, even if they are vital in the long run.

Poorly designed mergers could result in larger, less manageable programs that lose thematic coherence and undermine domain-specific expertise. Consolidation, therefore, would be strategic – not automatic. It would be driven by a clear assessment of which priorities benefit from integration, and where maintaining separation adds value.

Rather than aiming for maximum integration, the ECF would follow a model of smart consolidation, grounded in the following principles:

3.1 Define a clear thematic scope

The ECF needs to begin with a clearly defined scope: What problems is it meant to solve, and what priorities does it support – or explicitly not support?

The goal is to bolster the EU’s broader competitiveness strategy. To stay focused on this objective, the ECF would include only those programs that directly advance innovation, economic competitiveness, and industrial development. Folding in unrelated initiatives – such as LIFE (focused on environment and biodiversity) or the Union Civil Protection Mechanism (disaster response) – would not enhance coherence. On the contrary, it would likely create confusion by combining instruments with fundamentally different goals and methods.

A clear focus is essential for the ECF is to have real added value. With little prospect of a major increase in EU funding, difficult choices have to be made – not only about what to fund, but also about what to leave out. Europe’s strengths in technical expertise, research infrastructure, and its vast internal market provide a solid base. But capitalizing on those assets requires political discipline: clear prioritization, concentrated resources, and alignment across instruments and policies. Spreading funding across too many goals may be politically expedient, but in practice it weakens impact and undercuts the strategic clarity the ECF is meant to deliver.

The ECF would also remain an excellence-based fund – awarding support competitively rather than allocating it by member state. This ensures quality and efficiency but comes with distributional consequences. Stronger member states, with robust R&I ecosystems and better infrastructure, are more likely to benefit. This can widen regional disparities and reinforce existing innovation gaps across Europe. That said, this does not mean the ECF should be tasked with solving cohesion challenges. Instead, participation and regional convergence objectives would need to be be pursued through separate programs. Instruments such as Widening Participation and Strengthening the European Research Area are specifically designed to build capacity and in less research-intensive regions. While these programs play an important role in fulfilling the EU’s convergence objectives, they are best placed outside the ECF, which need to stay focused on excellence-based competitiveness and innovation.

Finally, any consolidation effort under the ECF needs to safeguard the independence and integrity of fundamental, curiosity-driven research. Flagship initiatives like the European Research Council, the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions, and the Research Infrastructures program operate through bottom-up, peer-reviewed selection processes. Their effectiveness depends on their autonomy and ability to fund the best science, regardless of thematic alignment. Therefore, it would be preferable for these programmes to to become part of the ECF but instead form an independent successor to Horizon Europe, which strictly limited to curiosity-driven frontier research.

3.2 Create thematic pillars and build instruments that cover the full innovation ecosystem

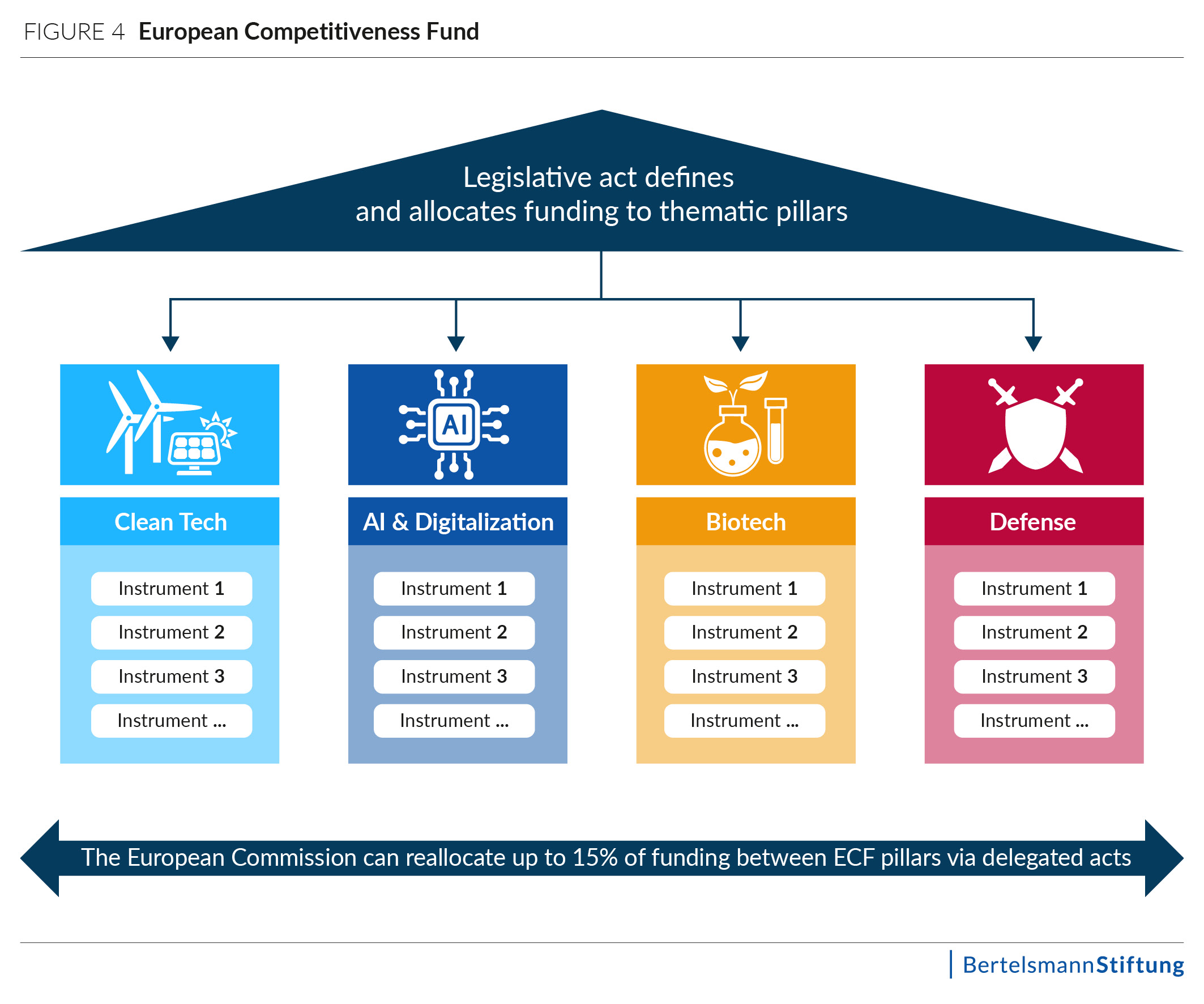

The ECF would be organized around four to six thematic pillars. These would be defined by the co-legislators in the ECF regulation, which would also set the financial envelope for each pillar over the MFF period.

Potential thematic pillars could include:

- Clean Tech and decarbonization

- Digitalization and AI

- Biotechnology and health

- Defense and dual use goods

Within each pillar, the Commission would propose individual funding instruments, subject to two conditions:

- Each pillar addresses the entire innovation ecosystem, that is, all stages of the innovation lifecycle plus enabling factors such as infrastructure.

- Instruments are clearly delineated to avoid overlap and ensure recipients understand which tool fits which purpose.

The instruments would not be defined in the regulation itself. Instead, the Commission would develop them and seek commitment appropriations through the annual budget process. This approach provides the Commission with the flexibility needed to adapt funding tools over the full MFF cycle – critical given that many future challenges are not yet fully understood. At the same time, co-legislators retain meaningful influence, as they can withhold funding during the budget procedure if they disagree with the instrument design.

Given the likelihood of shifting priorities over the MFF period, the regulation could include a “safety valve” for reallocating funds between pillars without reopening the legislation. A flexibility clause could allow up to 15% of each pillar’s budget to be reallocated to another pillar through a delegated act – subject to a legislative veto if the legislators disagree.

3.3 Use financing modes according to purpose

Each funding instrument within the ECF would be paired with the financial tool best suited to its specific objective. Grants would not be longer be the default option. Instead, for each instrument, the Commission would need to justify the funding mode chosen. However, leveraging private capital or de-risking investment is not a goal in itself. Public funding needs to deliver real added value – not simply subsidize what firms would do anyway or inflate financial figures through accounting tricks that make the ECF appear larger than it is.

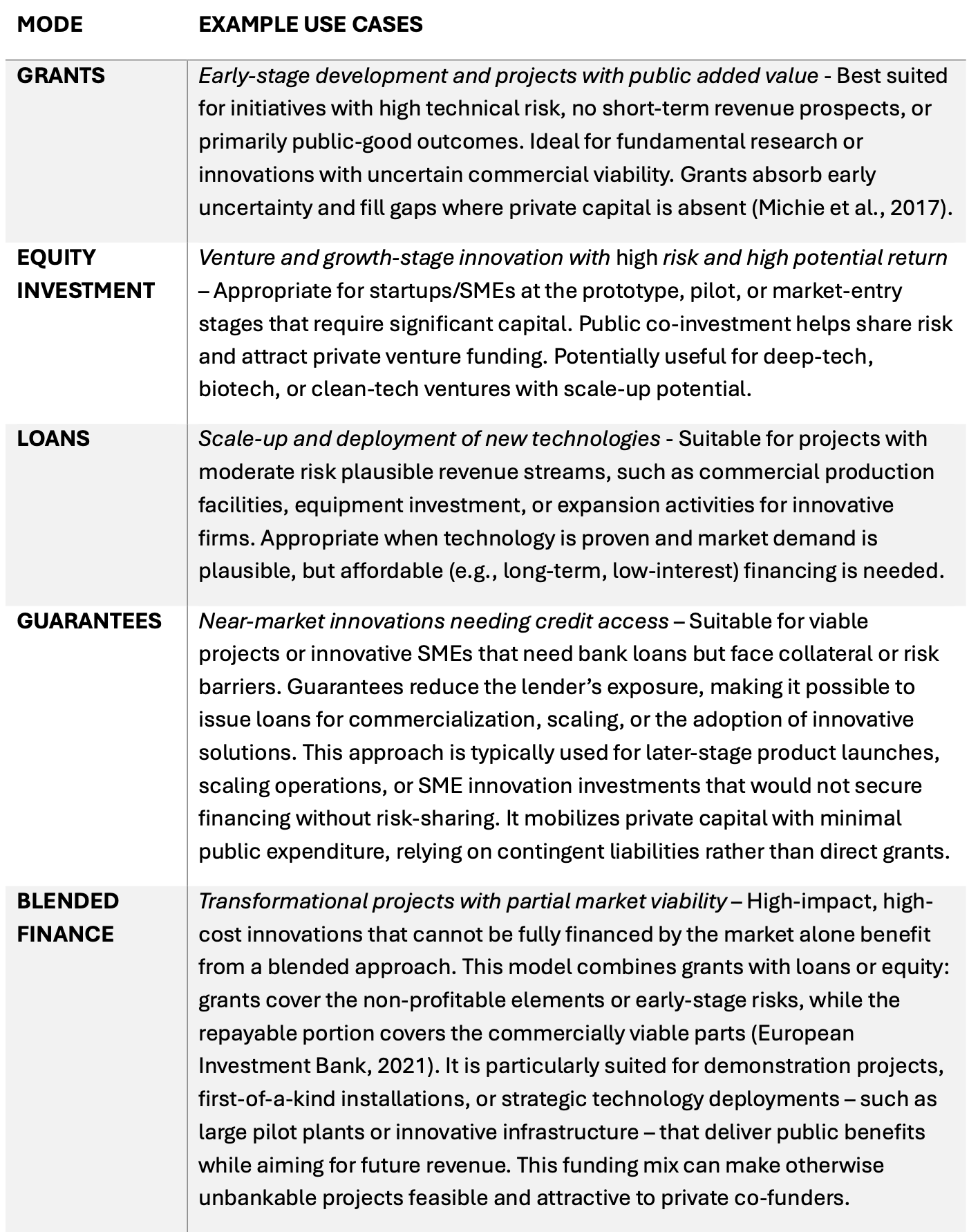

Possible financing modes include the following:

By matching instruments to project needs, the ECF can reduce overlap, avoid inefficient spending, and better target limited public resources, thereby ensuring support is deployed to the right projects, at the right time, using the most effective financial instrument.

3.4 Build clear and flexible governance

The pillar structure outlined above gives the Commission significant flexibility in designing individual funding instruments, since these will not be defined in secondary legislation. To ensure instruments are developed coherently while remaining responsive to the specific needs of each thematic pillar, the governance model would follow a two-tier structure: One DG within the Commission would take overall responsibility for the ECF. This central DG would ensure coherence across pillars, prevent overlap, and verify that all stages of the innovation ecosystem are adequately covered within each pillar.

However, the design of individual instruments would be a joint effort between the coordinating DG and the DGs with thematic expertise. These thematic DGs – those closest to the issue – would then take the lead in implementing the instruments, including preparing funding calls and making funding decisions.

Conclusion

The Commission is right to aim for a cleaner, more strategic funding landscape. But simplification is not an end in itself. The real challenge is to make the ECF work – not by collapsing everything into a single mega-fund, but by consolidating with purpose. That means setting clear boundaries on what belongs in the ECF and what does not; organizing support around thematic pillars that span the full innovation lifecycle; using the right financial tools for the job at hand; and enabling governance that is both clear and flexible. A smarter ECF can help move the EU’s innovation funding beyond today’s fragmented architecture toward a system that is not only efficient and excellence-driven, but truly transformative.

Download the policy brief here.

Kommentar schreiben