This analysis examines the emerging potential of a triangular partnership between the EU, Southern Neighbourhood (MENA) countries, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Based on the 2025 EuroMeSCo Euromed survey, it highlights four areas – clean energy, marine protection, secure connectivity, and conflict resolution – where joint investment and cooperation could yield lasting, region-wide benefits. A revived Union for the Mediterranean can serve as the new triangle’s coordinating body.

A missed opportunity – and a new hope

In the 1990s, the EU had a chance to shape the Mediterranean by partnership – but did not seize it fully. The USA, Russia, Turkey and especially China built influence in the region from the early 2000s. As a consequence of insufficient attention from the EU towards its Southern Neighbourhood, those relations became increasingly transactional, shaped by shifting alliances and short-term interests. By the mid-2010s, after intense support for the countries of the Arab spring, the EU had shifted into a merely defensive posture – reacting to crises and drawing its engagement to migration control.

The new European Commission, in office since November 2024, has signalled a shift. It seeks a more balanced, comprehensive partnership with the southern neighbourhood, though amid immense challenges. There are ten active conflicts across the region and mounting social and economic strain, including in and around Iran, Iraq, Israel-Palestine, the Kurdish regions, Lebanon, Libya, Sudan, Syria, Yemen and Western Sahara.

Today, the EU faces more challenges and competitors than it did in the 1990s, which were once considered a decade of opportunities. Yet, by seeking new partners in the wider neighbourhood the EU can still enhance its role. One key partner stands out: the Arab Gulf states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates).

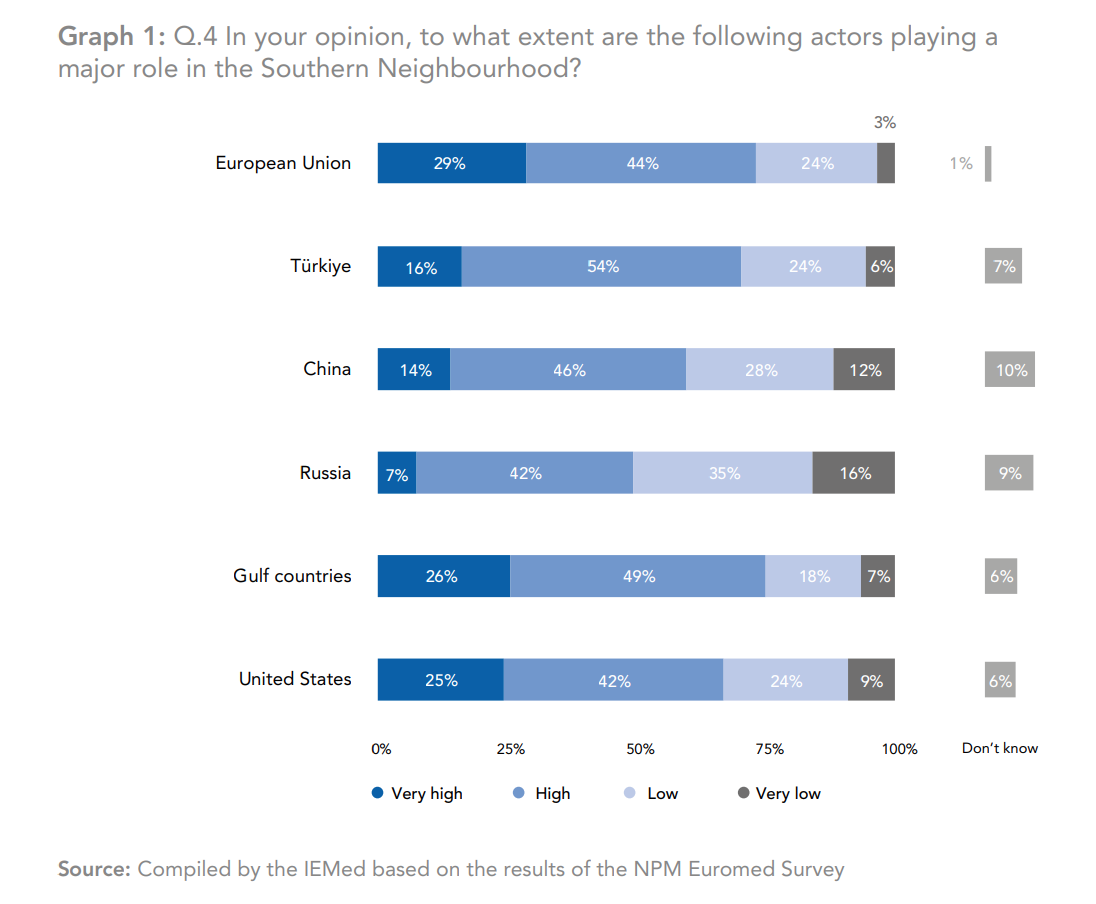

This powerful group plays a central role through growing investment, diplomacy and financial assistance. The 2025 EuroMeSCo survey confirms this shift: 75% of respondents rated the Gulf states’ role as “high” or “very high” ahead of the EU (73%) and Turkey (70%). While the gap is narrow, the trend is clear (see Table 1).

Table 1: Who are the major players?

The potential of the Gulf Cooperation Council and its member states

The central forum in which the wealthy Gulf states coordinate their activities is the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). As a regional organization headquartered in Riyadh and endowed with substantial sovereign wealth and significant regional influence, the GCC is an attractive partner for cooperation. However, the political and societal systems of GCC member states do not automatically align with EU standards on democracy and human rights.

Acknowledging the link between security and economic transformation, GCC states have intensified their role in regional conflict resolution. In the Gulf, they seek – even in light of the Israel-Iran war – to ease their own tensions with Iran by supporting US-Iran negotiations concerning Iran’s nuclear and missile programme.

Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia are part of Arab efforts to end the war in Gaza and advance political and economic reconstruction of Palestine. At the UN level, Saudi Arabia and France co-lead a Global Alliance advocating a two-state solution.

The Gulf’s diplomatic outreach also includes re-engagement with Lebanon and Syria, aiming to reduce instability in the EU’s Southern Neighbourhood. Beyond the region, GCC states – especially Saudi Arabia – have emerged as intermediaries in the Ukraine–Russia conflict, facilitating prisoner swaps and discreet negotiations.

At the same time, the Gulf faces major domestic challenges. Climate change, rising temperatures and water scarcity threaten the viability of long-term reform plans. In response, diversification strategies focus on building service-based economies and clean energy hubs, as demographic pressure and environmental stress mount.

EU-GCC partnerships in detail

The EU’s institutional framework for partnership with the GCC is set out in the 2022 Joint Communication on a Strategic Partnership with the Gulf. It identifies six core areas of cooperation: prosperity, green transition and sustainable energy security, regional stability and global security, humanitarian and development assistance, people-to-people ties, and enhanced institutional collaboration.

These priorities align with many of the political and economic challenges in the EU’s Southern Neighbourhood. In particular, the communication highlights the importance of joint engagement in promoting “peace and stability in this wider region”, explicitly naming Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Libya, Lebanon, Israel-Palestine, Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan as focal points for cooperation.

GCC member states are already investing in the EU’s Southern Neighbourhood. For example, the UAE is co-financing Israeli gas field development, Qatar intends to invest in gas interconnectivity through Syria, and the UAE and Saudi Arabia are backing the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEEC). This is a major infrastructure and connectivity initiative that aims to link South Asia with Europe via the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Additionally, startup collaboration initiatives have been launched between Qatar and the UAE with Lebanon, Tunisia, and Morocco.

While the EU is formulating the New Pact for the Mediterranean, the GCC is simultaneously deepening its political and economic engagement in several countries of the EU’s Southern Neighbourhood. Ultimately, the strengths of the EU and the GCC could be more effectively combined within a triangular partnership framework.

How to make triangular partnership work

Based on the EuroMeSCo Euromed survey 2025, four areas offer entry points for triangular cooperation:

- Alternative energy production for a post-fossil-fuel society: Developing and deploying wind, solar, hydro, biomass, and geothermal technologies to diversify energy supplies and accelerate decarbonisation. Further details are available in this study.

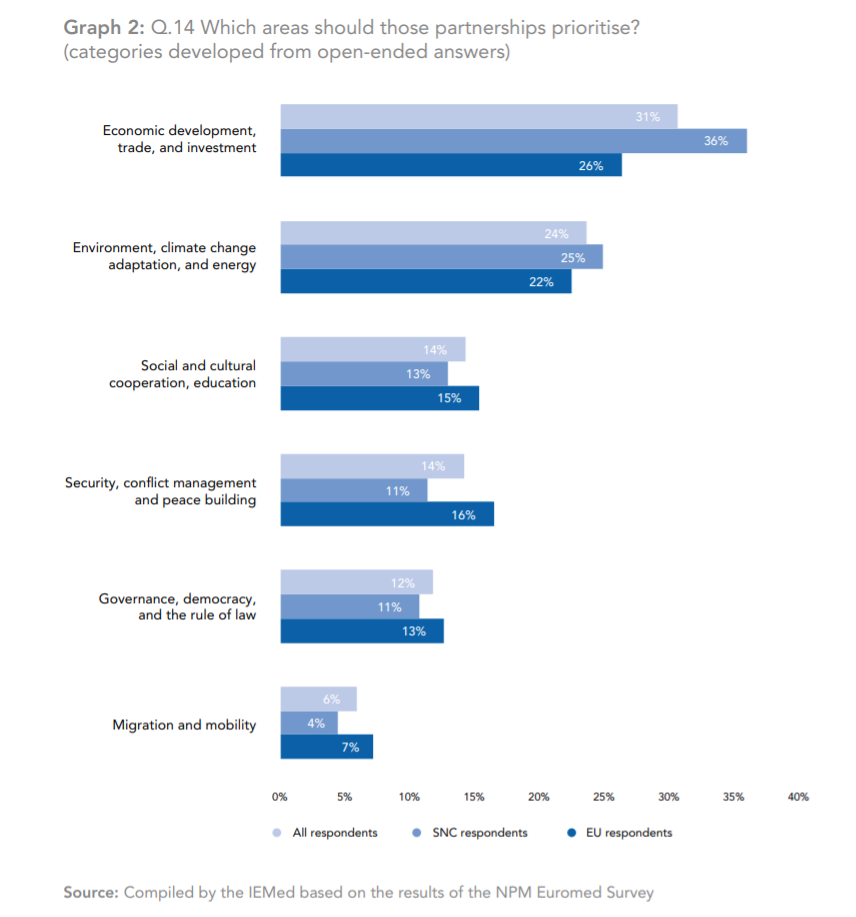

- Protecting marine environments: Cleaning and preserving shared marine spaces of the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Arabian Gulf. Together with alternative energy, this aligns with growing prioritisation of environmental protection, climate-change adaptation and the green energy transition (see Table 2).

- Secure trade routes and enhanced connectivity: Jointly safeguarding maritime and overland corridors and expanding transport and digital interconnections, reflecting the importance of economic development, trade and investment (see the first thematic focus in Table 2).

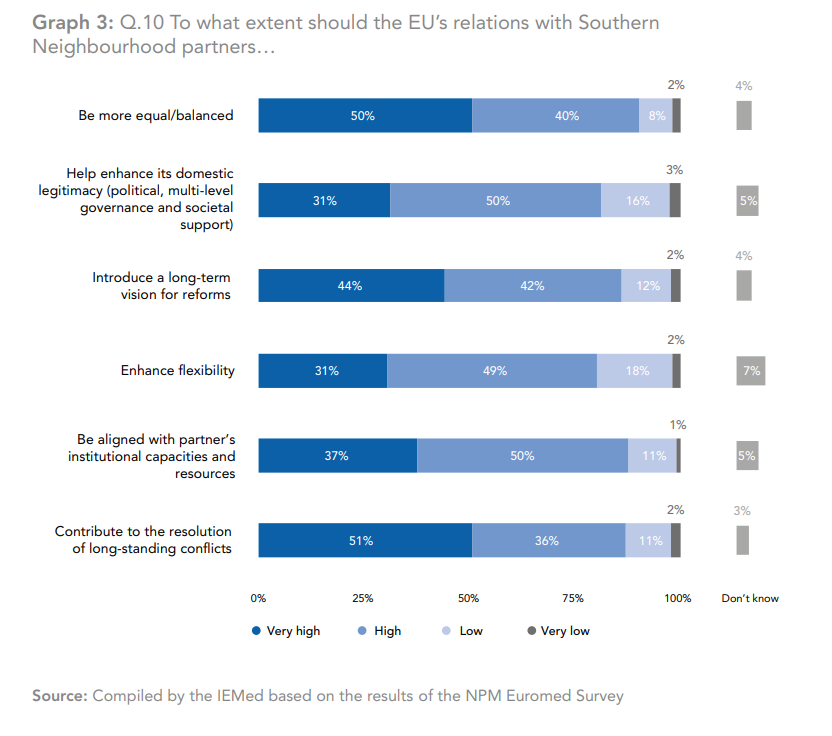

- Political and diplomatic conflict resolution: Coordinating efforts to address the ten ongoing wars and conflicts across the MENA region, including Iran, Iraq, Israel-Palestine, the Kurdish question, Lebanon, Libya, Sudan, Syria, Yemen, and Western Sahara. This resonates strongly with survey respondents: 87% expect the partnership to help resolve longstanding conflicts (see Table 3).

Table 2: Priorities for partnerships

By concentrating on clean energy, marine protection, secure connectivity and peace building, triangular cooperation can start to deliver tangible benefits for all partners of the three regional groups.

Table 3: What should the relationships look like?

The three regional groupings can pool resources into thematic investment funds. For the EU, this can be done through its 2023 Global Gateway initiative. Meanwhile, the GCC can achieve this via its substantial sovereign wealth funds. Joint innovation centres could then be established to advance shared regional economic and environmental projects.

But a triangular partnership will only succeed if project collaboration is truly equal. This view is reflected in the survey with 90 % of respondents calling for “more equal/balanced” relationships (see Table 3). In particular, the Mediterranean countries must not be left behind by the two financially stronger blocs. Ultimately, each partner should feel like an active contributor, not a passive observer, in the partnership.

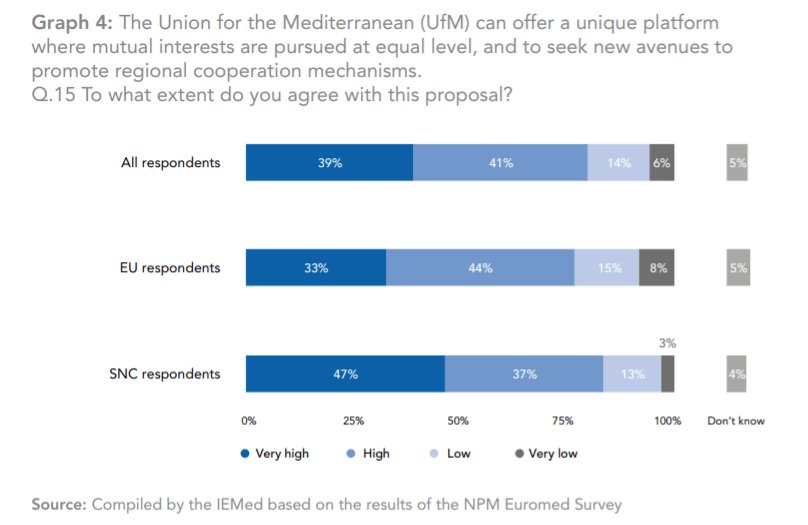

Revival of the Union for the Mediterranean

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) can serve as a framework for embedding the proposed triangular partnership. Triangular projects could be integrated into the UfM’s core Mediterranean framework, while allowing for the flexibility to involve GCC member states. The survey shows strong support for this approach, with 80% of respondents rating the UfM’s potential “very high” or “high” and agreeing that it “can offer a unique platform where mutual interests are pursued at equal level, and to seek new avenues to promote regional cooperation mechanisms” (see Table 4).

Table 4: The potential role of the UfM

A solid example of triangular cooperation within the UfM framework is the 5th UfM Energy and Climate Business Forum, held in May 2025 in Kuwait. It brings stakeholders from the Euro-Mediterranean and Gulf regions together to address challenges in energy transition and climate resilience, fostering cross-regional collaboration and private sector cooperation.

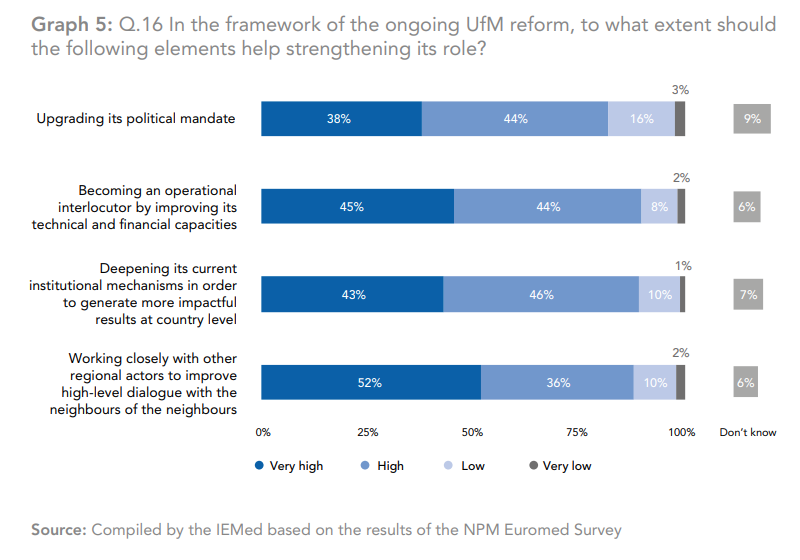

Within the UfM’s ongoing reform process, organisational capacity can be reinforced through measures that could enable it to support proposed triangular projects. A strong majority of respondents (88% rated it “very high” or “high”) agreed that the UfM should collaborate closely with other regional actors “to improve high-level dialogue with the neighbours of the neighbours” (see Table 5). This widespread support reaffirms the UfM’s potential role as an interface forum linking the three regional groupings.

Table 5: Strengthening the UfM’s role

If the UfM’s reform process takes longer than expected an alliance of countries from the EU, the Southern Neighbourhood Partner Countries, and the GCC could take the lead. This coalition would assume political, financial and administrative responsibility for specific triangular projects, such as the cleaning and protection of the Red Sea waters.

Conclusion

A well-balanced triangular partnership between the EU, the Southern Neighbourhood, and the GCC has the potential to turn shared challenges into joint opportunities. By aligning strengths and pooling resources through thematic investment funds, joint innovation centres, and a revitalised UfM framework, this cooperation can advance clean energy, safeguard marine ecosystems, secure trade routes, and promote conflict resolution.

But impact depends on inclusion. Success will only be possible if Southern Mediterranean states are equal partners; if they are not recipients, but co-creators. With genuine reciprocity at its core, this triangular model could evolve into a catalyst for resilience, prosperity and sustainable development across the wider Euro-Mediterranean-Gulf region anchored in shared interests, driven by joint ownership, and open to the future.

About the authors

Christian-Peter Hanelt is Senior Expert Europe, Neighbourhood and the Middle East, Bertelsmann Stiftung’s “Europe’s Future” programme.

Nico Zillekens is a political scientist and intern, Bertelsmann Stiftung’s “Europe’s Future” programme.

This text is based on a publication in the context of the 2025 EuroMeSCo Euromed survey and is available here in a slightly modified form.

Kommentar schreiben